Chapter 1. Sleepwalkers

There’s a time when the sea subsides—the sound of the wave becomes so far and faint that to get a glimpse of it you need to tilt your head to the side a little. Just like we were told to do with seashells when we were kids. Difference is, sometimes it’s not the Moon’s whim that shrinks tides. It may mean that something is changing, if we are lucky enough to be able to listen. 2020 started like this, with a wave smaller than what it was supposed to be, that became the largest one any of us had ever seen. It was not the Moon, but the tsunami.

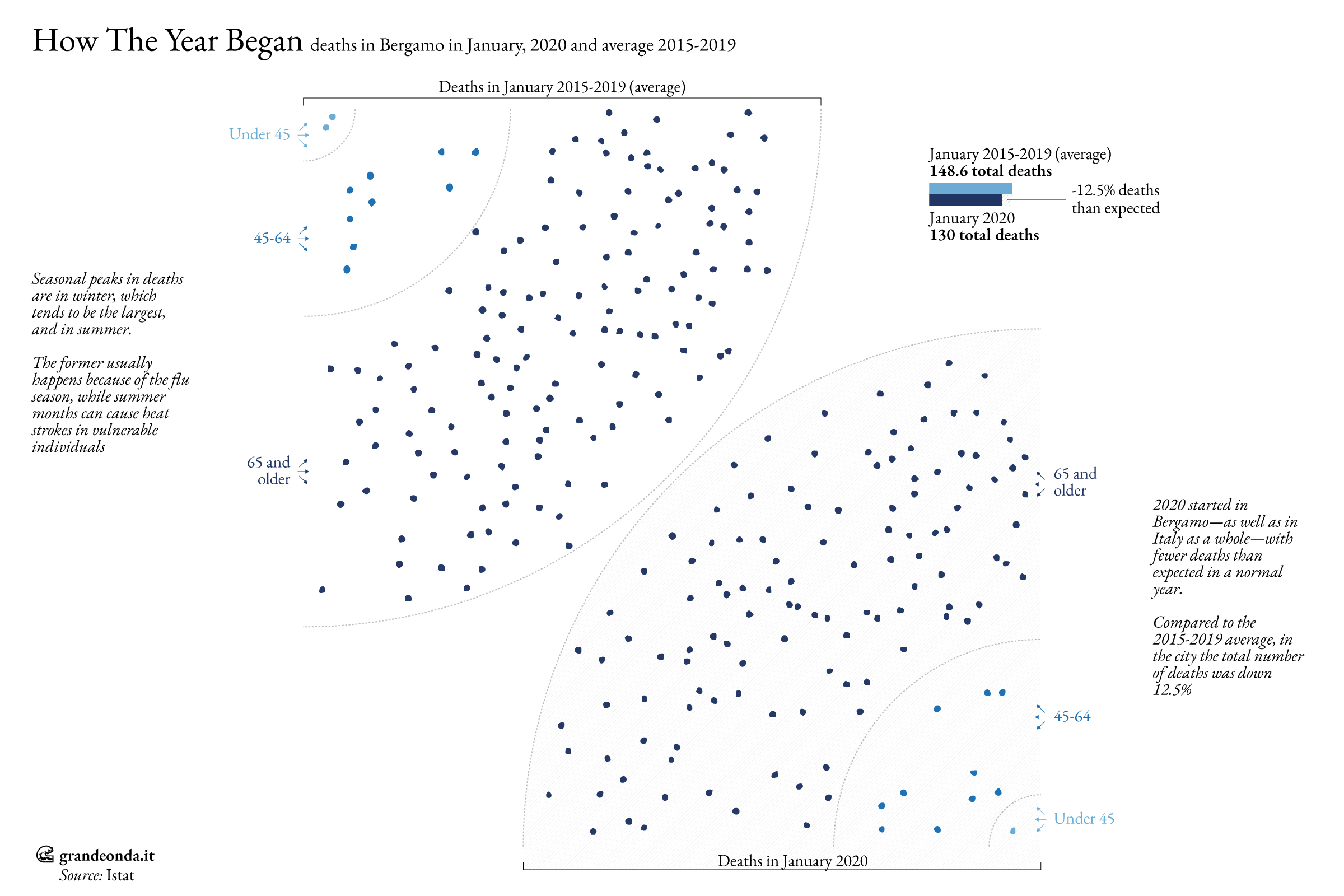

There are several cycles like tides, and many are taken for granted just because they are under our nose all the time. More babies are born in late summer because, you know, people have to keep themselves warm in winter somehow. On the other hand, the first months of the year are a time of flood, because that’s when seasonal flu takes its toll, especially for weaker seniors. After that things calm down until summer, when there is another smaller wave due to the heat.

It had been a lucky January in Italy, actually one of the best in recent years. Sooner or later the wave always comes, but for some reason this time it had been gentler than usual and thousands were spared. Like fractals, that repeat their geometric pattern as you watch them closer and closer, this was true for Italy; as it was for Lombardy; as it was for Bergamo.

There was news of some pneumonia outbreak in China already, its origin unknown, but it was distant news. As it’s always the case, at first we didn’t know much about the virus, but then new evidence started to emerge. It almost always turned out for the worst. A few dozen cases were found in a seafood market in Wuhan, where the virus could have jumped from animal to humans. As they became hundreds in just a few days, this hypothesis was shaking already. “It would be unlikely in my mind, given what we know about coronaviruses”, said the epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, “to have animal exposure be the principal cause of such a number of human infections”.

On January 20th a Chinese team confirmed that human to human transmission was possible. Soon Chinese scientists started to talk about asymptomatic transmission as well, a catastrophic scenario that would make this new virus way harder to contain as compared to the one that caused SARS.

(Just a week before Chinese authorities denied that human to human transmission was happening. During the 2002-2004 SARS epidemic the Chinese government already behaved with extreme opacity, hiding or even forging important data. This time, too, it made more and more complicated for the world to trust even the information that was true.)

Communication by health authorities was reassuring. On the same January 20th Giuseppe Ippolito, director of the Spallanzani National Institute for Infectious Diseases (Rome), explained that “according to the European CDC the risk of importing and spreading the new virus is extremely limited, and this is also true for Italy”. Giovanni Rezza, expert in infectious diseases at the Italian National Institute of Health, said that “overcrowded places are to be avoided and people need to wash hands often. The use of face masks might be considered. Obviously I’m talking about people traveling to those areas, because here there’s nothing to worry about at the moment”. Ippolito, on January 21st, also said that “contagion needs to be considered only for those who traveled to China”.

This was also Italy’s stance. For months official policy recommended tests only to people that had direct contact with the Asian country.

Probably we’ll never know why the focal point of COVID-19 in Italy developed right around Bergamo. Epidemics are so complicated that forecasting their exact behavior would be like wanting to know how many millimeters of rain are there going to be on the Coliseum this exact day in 200 years at 18:03. Flu is more predictable, at least. With a virus that behaves like SARS-CoV-2 it would be even harder.

But if we really wanted to find a place with the ideal environment for the virus to take hold, this was the Seriana Valley around Bergamo. It had an airport that in just a few years became Italy’s third largest, from which it radiated a growing network of activities. People coming and going from all around the world, meetings, contacts, handshakes. Routine.

At that moment in January, however, nobody would still shudder while seeing two strangers chatting up at a close distance, in a closed room.

Meanwhile the virus did the only thing that a virus can do: it replicated and spread. New cases were found in Thailand, Japan, South Korea, then in the United States, in France and Australia.

The violation of the official testing protocol allowed to find the first Italian case, a 38-year old in Codogno (Lodi), admitted to the local hospital with a pneumonia that didn’t seem to get better through usual medicine. Two SARS-CoV-2 positive Chinese tourists were discovered earlier in Rome, but this was the first patient that never had direct contact with Asia. If one was found, with so few tests available, very likely there were many more.

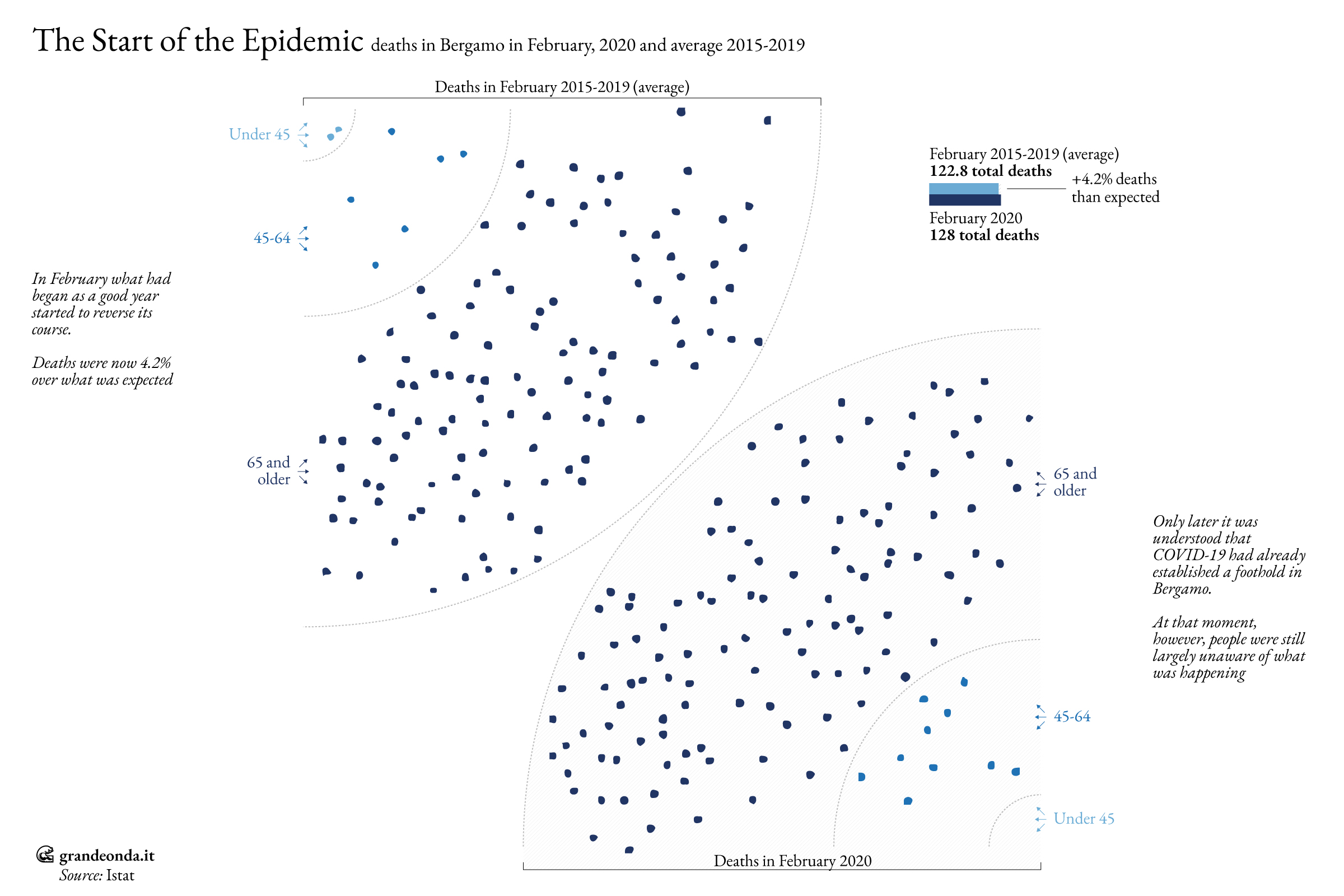

Numbers however do not self-generate, and they always show what people are looking for. For months nobody expected COVID-19 and so nobody was looking for it. Only later we came to realize that at that moment it had been spreading for quite some time already.

“I got the coronavirus between the February 10th and 15th”, doctor Cesare Maffeis said, “I thought I had a simple flu. I have never taken a sick day in thirty years of work. I connected the symptoms later, but I couldn’t believe I had the coronavirus. I’m sure I got it from a 92-year old lady that I visited in her house and then unfortunately passed away. She was among the first to die in the province of Bergamo with an official COVID-19 diagnosis”.

Francesco Zambonelli, son of two people that died of COVID between February and March, recalled that “my mother was already sick on February 3rd, when she went to the ER in the Alzano Lombardo hospital. It’s the closest hospital to Villa di Serio, where both my parents and I lived. Nobody was talking about the virus, so nobody thought it could have been dangerous”.

On Sunday February 23rd tests at the Alzano Lombardo hospital showed the first two positive results in the Bergamo province. Giorgio Gori, city mayor, remembers them this way: “when I heard about the first two cases Alzano Lombardo appeared almost far away. That’s a paradox, since it’s only a few kilometers apart from Bergamo”.

That afternoon the governor of Lombardy Attilio Fontana and the regional surgeon general Giulio Gallera summoned all mayors. They were to meet in the main city of their provinces. More than 200 mayors from the Bergamo province met behind closed door, crowded inside the Giovanni XXIII congress center. Silvano Donadoni, mayor of the small town of Ambivedere and its 2,400 people, was the only one wearing a mask. A local public health manager saw him and asked what he was doing dressed like that, then burst into laughter.

The low tide had already begun to reverse its course. The number of deaths had grown over the level of previous years, wiping out whatever luck January had. It was a process too slow and pervasive for anyone to notice while they were in it. It was also something that was not supposed to happen, because usually there’s no reason for so many people to die all at the same time. Yet it happened.

As the days in February go you can feel in the air this vague, sinking feeling that something’s wrong. It’s like slowly drowning. Cases go up, the pressure rises, but the instinct of the mind is to get away from it all. It’s just China’s problem. Just Codogno’s problem. Just Bergamo’s problem, just Lombardy’s. How close could it possibly get?

For what it’s worth I was a sleepwalker, too. It took me some time before realizing, just as everybody else. I didn’t imagine anything, didn’t foresee anything, didn’t know anything.

At most I remember a moment, that month, when I went to celebrate Carnival in a small town in Piedmont. My friend’s girlfriend had a bad cough, but nobody really noticed. “I’ve had it for a few days now and it doesn’t want to go away”, she said to me at some point. There were lots of people in the streets, jumping up and chasing wagons with their music. Looking at them I had the most fleeing moment of uneasiness, and like in a restless dream it felt like I could wake up any moment, before shrugging and getting back to the dance.

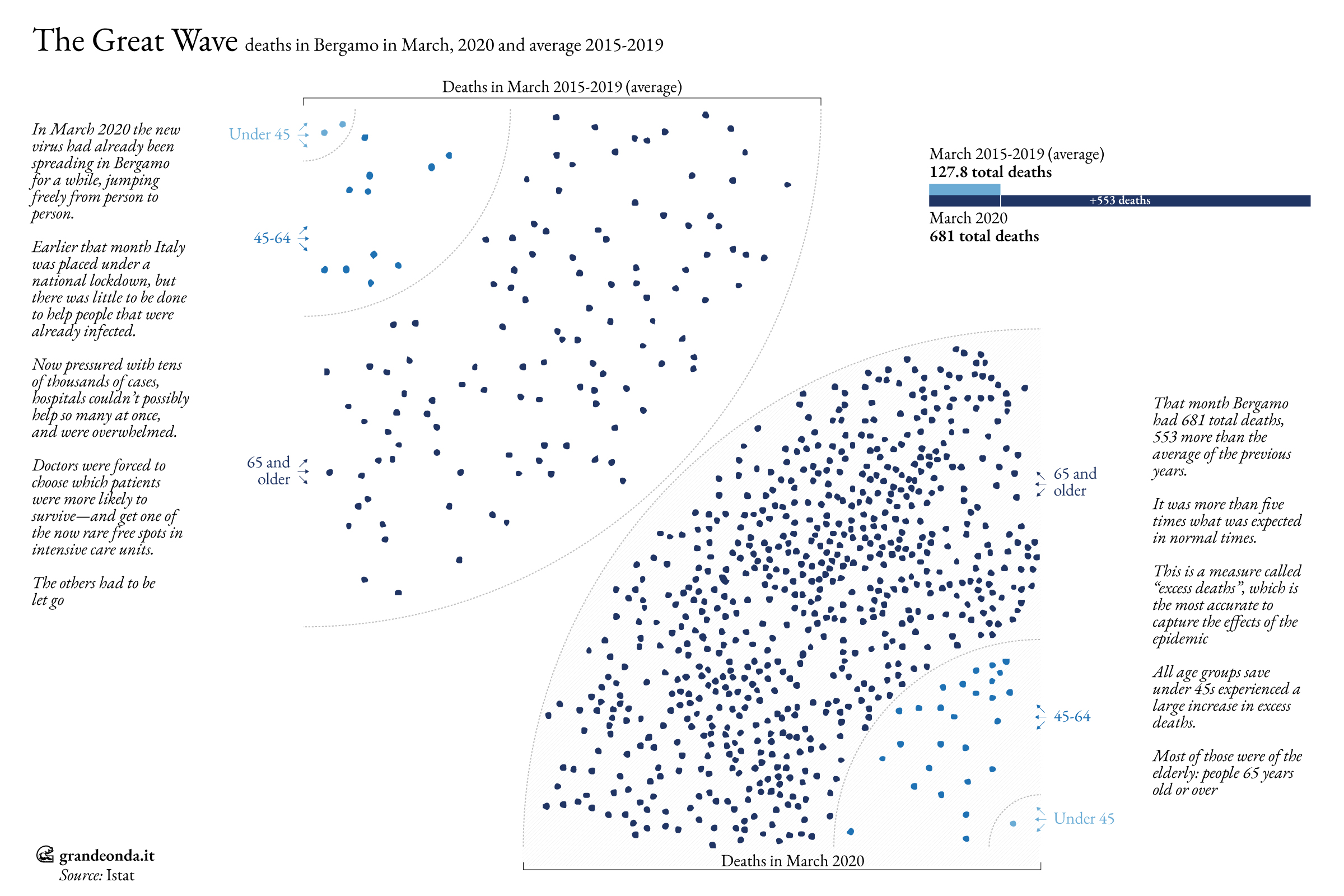

An epidemic is so dangerous because nothing happens until everything happens. The great wave fed on bodies, growing exponentially doubling after doubling, until in March it became the largest blue mass we’ve seen in decades. As in wartime, there were no more good decisions but only some less bad than others.

Crushing Bergamo and its valleys was a disaster that many of us were not able to foresee. The sum of the unimaginable, of the worst fears and bad decisions that just in the city tore apart hundreds and hundreds of families.

It was point zero where everything breaks down, there’s no society, no support, no connection, nothing. The only thing left is the desperate search, for ourselves or our loved ones, for a scrap of wood to keep us afloat.

Counting those people with numbers maybe feels like a brutal and meaningless act.

Every time somebody dies voids are born, as small or large as others felt close to that person. It’s the weight of survivors, an idea that brings to mind something that happened to me years ago.

One evening my girlfriend at that time told me that her father was very sick and there was nothing to do anymore. She wasn’t even 20 years old. The day of the funeral I waited outside the church, because at that moment as a non-believer it seemed like the right thing to do. Not that I had the slightest idea of what to do, to be honest.

Years later, when we broke up after a very happy time together, she told me how lonely she had been feeling those days. I don’t know if I could have done more, if anybody could have done anything, but it doesn’t matter. The guilt never went away, and I don’t think it ever will. Only this way did I learn one of the most obvious lessons, in the stupid and slow way it takes sometimes to learn obvious lessons.

Funerals aren’t meant for the dead. They are meant for the living.

Chapter 2. Survivors

The hospital I visited more often was the most beautiful I had ever seen. It had a nice fountain in the hall, a very silent lift in transparent glass, a solid tinder roof. Wide windows through which you could see the woods outside, the nice dark red of leaves in the December wind. It didn’t take much imagination to see in it a nice holiday home in the hills, to run to as soon as you’ve got a free day at work.

Every place would have been better than the hole my mother was in before, where they even forgot the right time to give her meds.

In weeks and weeks of visits, both in flood and in reprieve, the impression I had was always emptiness. A nod to the person guarding the thermal scanner, a “thank you” to the nurse that got the clean clothes. A meager second of human interaction before the big red door closed the ward again, and that was it for the day. No people wandering around, no noises, no distractions.

In a hallway there were a few perfectly arranged chairs, like in an auditorium or a concert hall, that reminded me of Chernobyl after the evacuation. During those months the hospital looked like a place where the time of people seemed to be over so fast that it was as if they had gently disintegrated only a moment before, without a trace, while the rest of the world didn’t even have the time to realize anything yet.

Silence comes in different types. The one of overwhelmed hospitals during the pandemic was not a silence of quiet or peace, but one of sweat, tears and labor. The one that didn’t give you time to catch your breath. The same one that was in my home the night before my mother’s surgery, of a different quality than any other silence I had experienced before. Behind every closed hospital door patients after patients after patients piled up. Even the most seasoned staff had never seen anything like it.

The virus takes a sane body, billion years of evolution, and turns it into a silly machine, a puppet whose only purpose is to copy it to oblivion. Left to itself, it does not only infect people, but also the entire society until everything is COVID. First a cell, then an organ, a patient, then three, eight, the whole ward, hospital, city, region and country, continent and planet—to the very last corner. First, it’s just one person’s life that starts revolving around the illness, then it’s labor, the economy and the society. Everything gets swallowed, an infinite hunger machine, from the biggest issues to even small talk that always ends up about talking about that. The physical contagion is in the body, but the effects of the pandemic force the human species to become COVID species until further notice. Everything else becomes irrelevant and needs to be put on hold.

In our collective memory the idea of what it means to fight against this kind of enemy doesn’t exist anymore. There are no statues, ceremonies, days of remembrance, and what little is left has been in the shadows for decades if not for centuries. “Our historical memory of epidemics is short, and that’s natural”, said Jessica Play, who oversees historical quarantine stations on the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. “It’s the memory of death and suffering, things we would rather not think about.” That’s why we’ve never seen a half-staff because something like this happened at most a hundred years ago, too many generations back to think it might happen again. Who even has a grandfather or grandmother that told that remote story, when people died maybe more for a virus than for the war to end all wars?

“The Forgotten Pandemic”, somebody called it. Too distant in time to remember that among all crisis in human history the one against diseases leads us to the most inhuman and indifferent of enemies. Even the most savage killer, ruthless dictator—hungriest animal—can have perhaps the smallest grain of something to identify with. But against illness there is no diplomacy or negotiation, trick or reason, pleading or compassion. Some people tried like there was an election to win, but in the end the reality is simple enough: you can’t cheat a virus. So, our species regresses to its coldest, brutal imperative.

Pure, simple survival, where losses only matter for one side.

After the first wave and a summer with a surprised, confused reprieve, autumn brought the second to Italy. This time it was not a tsunami focused only on some areas, but a full flood that even got to those who were spared during the spring. Many knew this could happen, that it was likely, but it didn’t help.

It lasted months, and ended up being way worse than the first time.

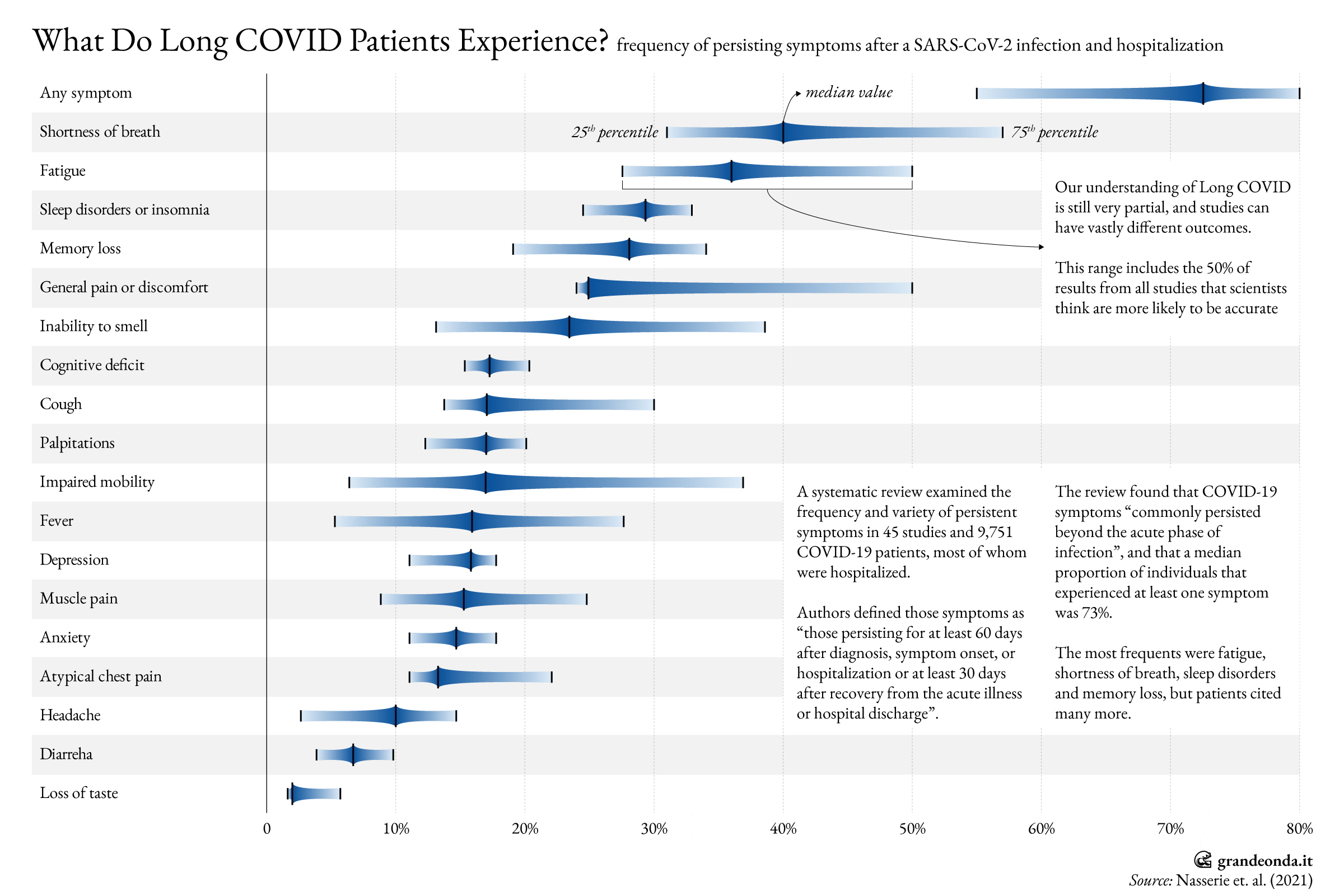

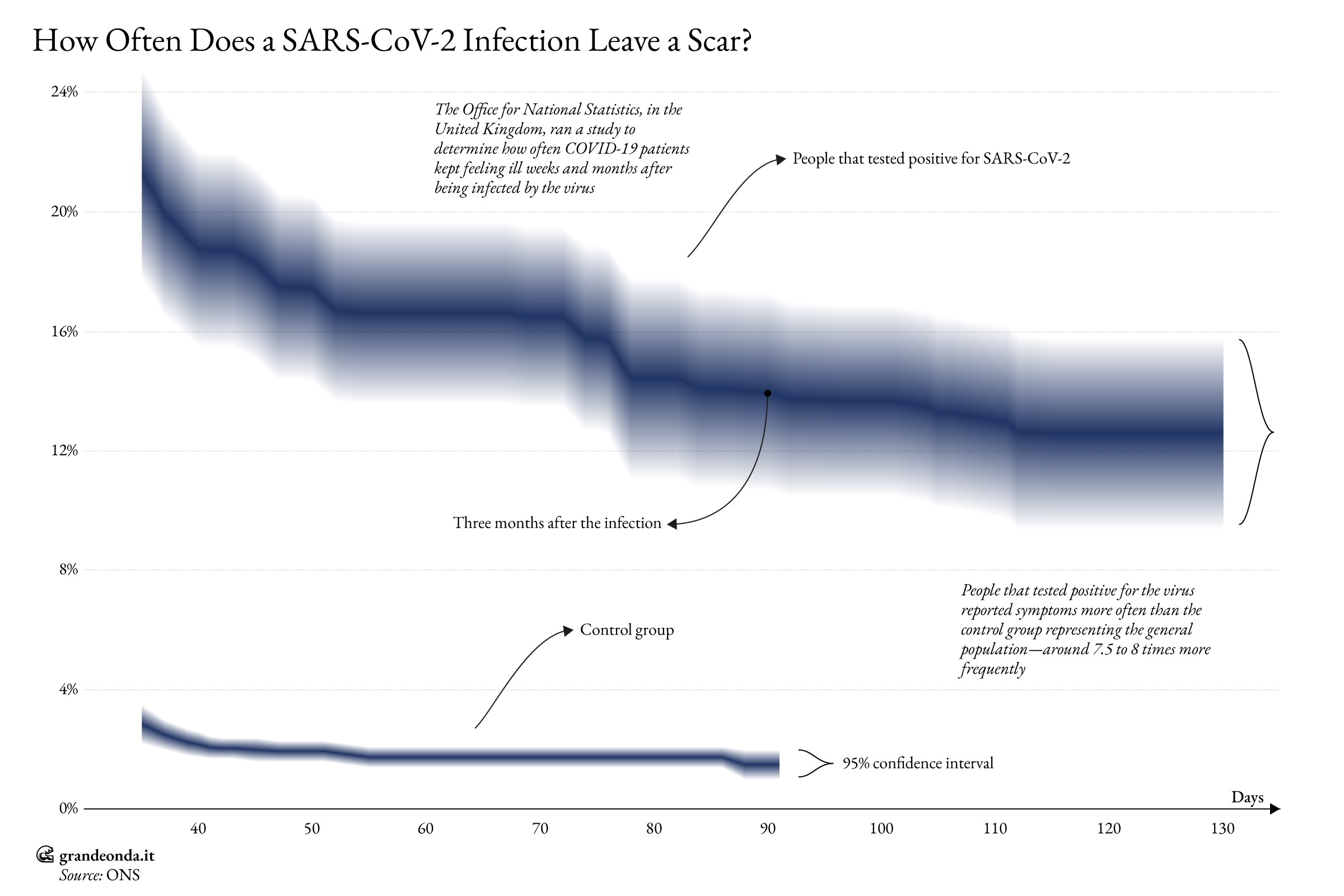

Deaths are perhaps the most glaring part of the epidemic, but for survivors even healing can be a complicated and painful process. One example is that constellation of symptoms that at some point we’ve come to know as Long COVID, which sometimes affects people after the acute phase of the illness tormenting them for months.

“At the moment it looks like Long COVID is caused by more than one process”, explained Domenico Somma, immunology researcher at the University of Glasgow. “We see that because some patients experience it during the acute phase of the illness already and go on like this for weeks and months. Others, however, start to develop symptoms after they are no longer positive to the test. The virus can affect different part of the body, not only lungs and the heart, and depending on the damage it can create lasting or even permanent symptoms.

In some people it can generate an abnormal response of the immune system, that destroys the virus but might create even more damage in the process. That’s what’s called cytokine storm, which can happen during the acute phase of the illness and is probably the cause of some Long COVID symptoms. The immune system managed to eliminate the virus but wasn’t able to turn itself off, and so it starts damaging tissues. This looks like why some people have Long COVID symptoms in their nervous system”.

Long COVID can go from a very mild discomfort to a series of severe and disabling issues. This extreme variability makes it hard to understand how often it presents and why.

The British Office for National Statistics tried to do that comparing two groups of people, one made of people positive to the virus and another one representing the general population. It turned out that members of the first reported feeling ill way more often than the others, even after months. As much as we don’t know exactly what’s going on, the evidence strongly suggests that this is real.

“The reason is still unclear”, added Somma, “but during the illness the immune system starts producing antibodies that attack the body just like what happens in autoimmune diseases. This process looks like what’s behind Long COVID symptoms to kidneys and joints. Lastly, even if somebody is no longer positive to the test the virus can hide in other parts of the body. This can cause other damage or keep the immune system on. Unfortunately Long COVID symptoms come from several processes, making it hard to study them and find a cure”.

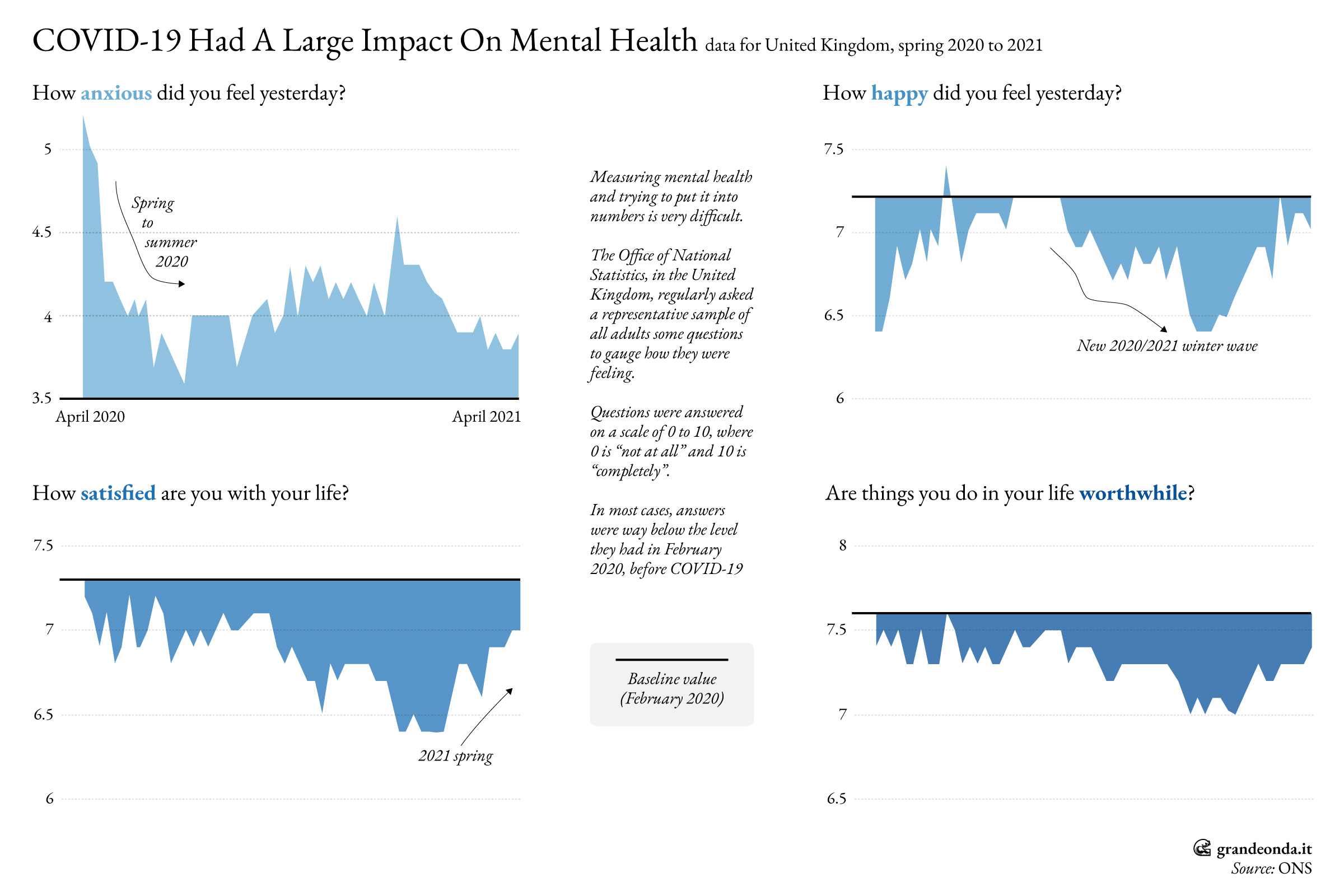

For who is fortunate enough not to get infected, there is still the mental toll. I can’t speak for others, but I can at least describe my experience: the horror and powerlessness of having to watch millions of people dying without being able to do anything. The paranoia of washing hands for the correct amount of time, until they become red from the hot water. The sticky, hot, disgusting air of my breath that comes back at me through the mask; the world as a vague blot filtered by steamy glasses. The estrangement and loneliness of living alone, away from family and without being able to see friends for months.

Too much even for somebody that feels alone even when he’s among people.

My mother’s cough as we talk, the obsession of her fever to the tenth of a degree while her doctor pretends it’s nothing. Times of emotional nothingness cut off by the need to cry, the feeling of having become a crystal doll that can be crushed by the smallest touch, a sand statue dispersed by the wind. A general, progressive sense of disintegration of the soul. Some bad ideas that it took years to put aside creep up again, relentlessly.

It’s something difficult to describe, that nobody can see but is just as real as needles, tubes, syringes and respirators.

Neuropsychologist Tiziana Metitieri explained to me that when talking about those issues we need to be very careful. “Communication about psychological distress during the pandemic was often scaremongering”, she said, “and it doesn’t only prevent people from getting accurate information, but may also amplify suffering and trigger a crisis in the most vulnerable people”.

On the one hand, she said, there are individual means which are paramount to adapt to adverse events and to the change the pandemic imposed on us. They reduce vulnerability to depression and anxiety. But there is also a group of people at much higher risk than others.

“A British study showed that being a woman, young, with a lower level of education or income, with preexisting psycho-pathological conditions, living alone or with kids were all risk factors for higher levels of anxiety at the beginning of lockdown. In the following weeks symptoms generally decreased, but differences between groups were still there at the end”.

At the same time, Metitieri noted, “the pandemic brought to light previously under-discussed psychological needs. Until a little more than a year ago it would have been risky exposing themselves to social stigma talking about fear, discouragement, trouble concentrating, sleeping or eating as a response to adverse events in life. Our shared sense of a lengthy time of discomfort made expressing it easier. Psychological and psychiatric disorders became more visible in the public debate”.

Those are very sensible topics, that like the issue of suicide can and must be discussed but always keeping possible consequences in mind. There was some talk about a growing numbers of people killing themselves, for example, but the neuropsychologist emphasized that “data doesn’t show any increase at the moment”, while “the trend will have to be monitored considering the economic crisis as well”.

In this sense “it doesn’t help a media campaign that at times even described suicide as an acceptable choice. That’s a potentially very dangerous signal, because we know that media can drive emulation. The message should be that through support a crisis can be overcome”.

The experience I wrote about is just mine, but I don’t believe it’s unique. I have seen friends in psychological conditions that I could have never imagined. Some of their stories resemble what happened to me the day of my mother’s surgery.

The day before the surgeon told us that given her conditions it was unlikely she’d survive. That morning I went out for a coffee with a friend, and despite me trying to push it back I started feeling something rise up from a specific point right in the back of my head. It was as if a thicker piece of plexiglas was falling on reality. Rationally I’m there with my body, but I feel as things are getting more and more distant. The nodal point arrives a few hours later, when I’m grocery shopping with my father. Ordering thoughts becomes difficult, impossible, until I’m short of breath. At that moment the universe becomes a single large block of white heat, shining more than a thousand suns, and I couldn’t say what two plus two is. It’s the extreme shortsightedness of the mind.

I wonder what would have happened if, at that moment, we didn’t get a phone call to tell us that surgery was over and my mother was alive.

What I know is that’s a kind of dissociation I wouldn’t wish for the person I dislike more. Multiplying this for the all the people that might have had it because of the epidemic and the isolation can give us an idea of how much invisible consequences can weigh. This is just what happened to me, and I’m one of the lucky ones. I’m not a parent, so I can’t even begin to imagine how many questions the people that were could have possibly had. Shall I send the kids to school? And what will they miss out if I don’t? Won’t we risk infecting the grandparents? I won’t even start asking if they were worried about getting the disease themselves, because I’m sure every parent would when their children’s future is at stake. Yet, who would take care of them if something happens to me? Would it be right to leave my partner doing this alone? And could them?

Questions over questions over questions, and no real answer.

Chapter 3. The Matthew Principle

You wicked and lazy slave! You knew, did you, that I reap where I did not sow, and gather where I did not scatter? Then you ought to have invested my money with the bankers, and on my return I would have received what was my own with interest. So take the talent from him, and give it to the one with the ten talents. For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away. As for this worthless slave, throw him into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth”.

The last part of Jesus’ Parable of the Talents, as told by St. Matthew in his gospel, described the words of a master to the last of his three servants. Before a long journey he entrusted them with some money—five, two and one talent respectively. The first servant invested them, earning the same amount, and so did the second. The last one, fearfully, hid his only talent in a hole, preserving it but without any profit. Upon this return the master praised the first two servants but punished the other, despite him being the poorest and most fearful.

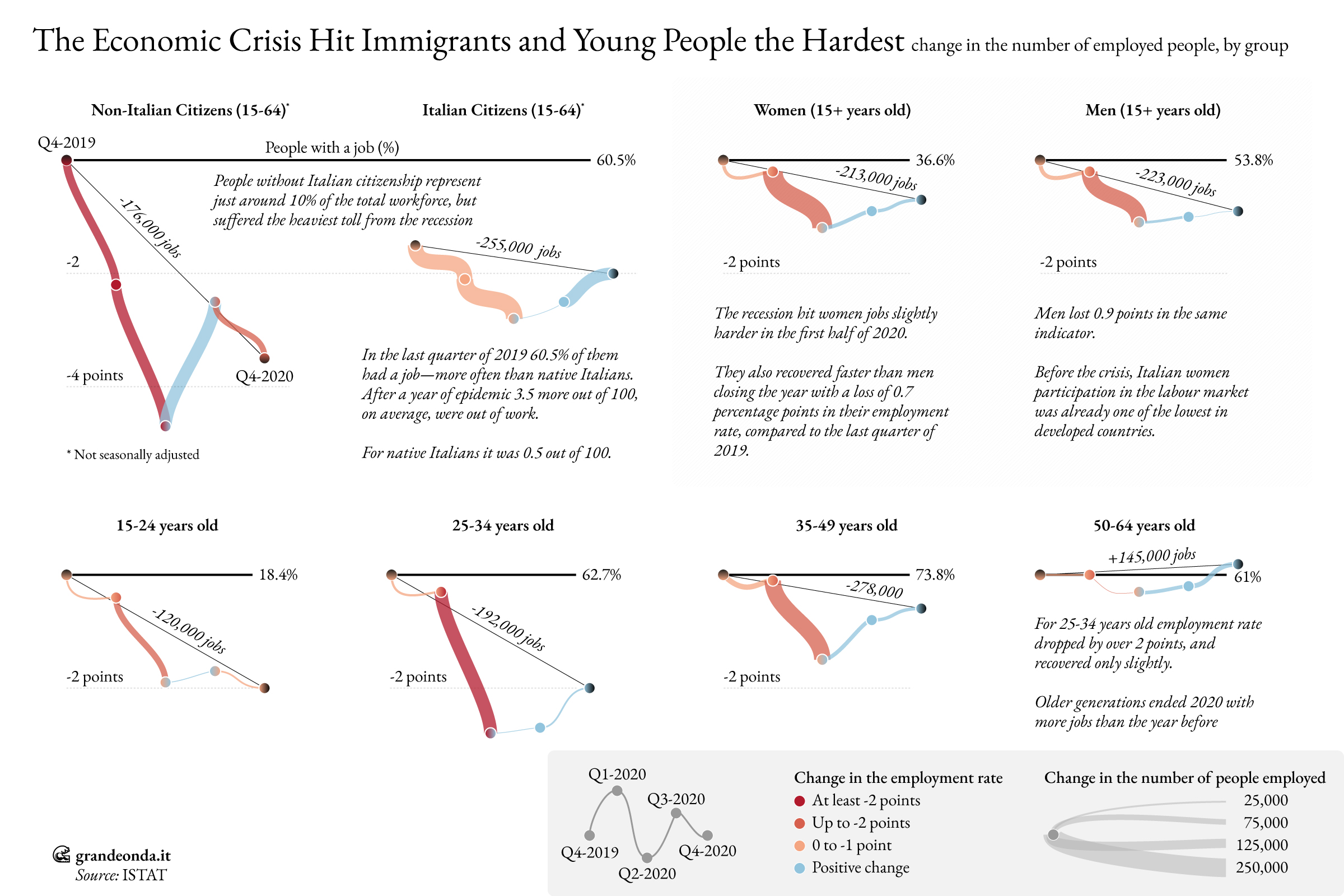

For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer, that’s the concept. It must not be easy for a theologian to justify this idea to a modern sensibility. But besides its moral teaching, it’s a principle at work every time there is a crisis. We saw the weakest groups in Italy—young people, women, immigrants, minorities—suffer the worst consequences after the 2009 recession, and then again recently after the health crisis has become an economic one.

Closing entire sectors to avoid infections and protect people’s health was perhaps a desperate decision, but at that point it was inevitable unless we wanted most of the population to get the virus. The effects of this choice sent off scale many indicators that we can usually rely on to understand how thing are going.

“Wide sectors of the economy were frozen”, explained financial analyst Mario Seminerio, “obviously there’s no comparison with past recessions anywhere in the world”. In 2020 the contraction in the Italian economy was the third worst among developed countries after Spain and the United Kingdom, two nations where the epidemic hit very hard.

“During the pandemic”, said Seminerio, “the closure of economic activities in Italy mostly hit the service sector, that is activities involving direct contact among people. This caused the collapse of the hospitality sector (tourism, restaurants) and commerce. Tourism has a pretty high incidence on Italian GDP compared to other countries, and this took its toll, too. The presence of a pervasive informal economy in the service sector, which also experienced a big blow caused by lockdowns, explains why Italy suffered so much. Manufacture held on and is now recovering, just like elsewhere, while the underdeveloped tertiary will suffer until the pandemic ends”.

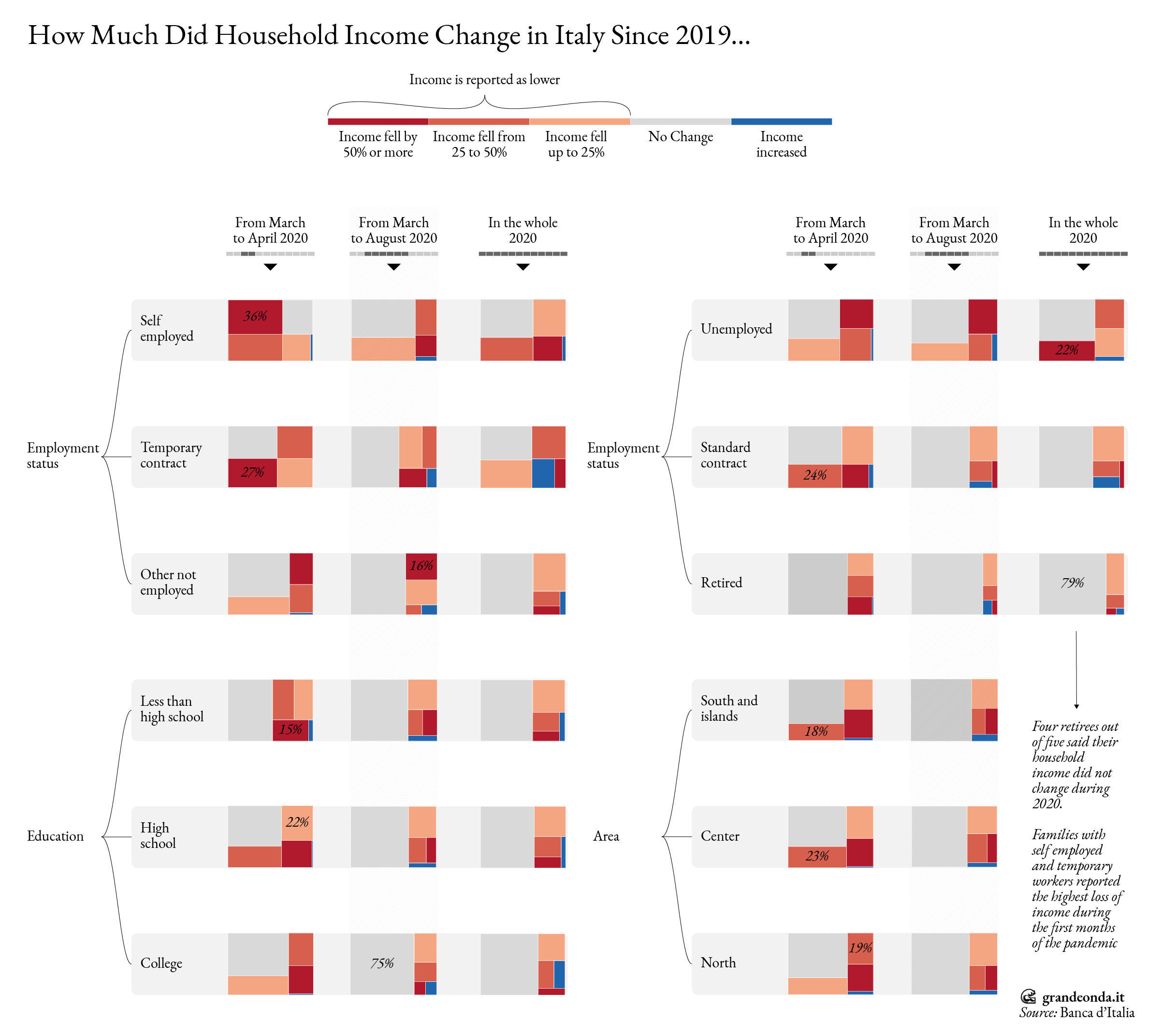

For Italians an important difference compared to other countries is that help from the government has been often rare and ineffective. It didn’t go always to those who needed it the most. Several countries set up measures to mitigate the effects of the recession, and the result was that in many cases household income didn’t fall.

In Italy on the other hand the welfare system works poorly, and the money spent tends to reach less the poor and more other groups. This was the case in 2020 as well, when according to an Eurostat analysis Italy was among the few countries where the middle class benefited from transfers more than the poor. This is not a new problem, by any means. A previous OECD study showed for example that the poorest get only 8% of monetary transfers, the richest 43%.

A situation like this hit Italian families in very different ways. Groups that were already in a difficult situation suffered the most, while others managed not to. We see this pretty clearly in the labor market, where many of the best paid jobs could easily be carried out from home. Elder workers were in a privileged position when it came to job protection and entitlements, and benefited from them losing little, while the opposite situation cost others a lot.

“As in all crisis”, said Andrea Garnero, labor market expert at the OECD, “younger people were the ones hit the most. This always happens because they have temporary contracts that make them easier to fire, or not get a new contract. There was some debate about the role of women, and even if there’s somebody interpreting the data a little differently I believe that they paid more than men. On top of this, and not only in Italy, they represented the majority of people working in healthcare, on the trench against the pandemic”.

Here there’s another historical problem at play. That is, the role of Italian women in taking care of a large part of domestic work and child care. And, conversely, the habit of Italian men to pay very little attention to it. The relationship between the two is one of the less equal among developed countries: Italian women spend on average one hour and a half more than men doing paid and unpaid work, every day. With school closures and widespread work from home it is entirely plausible that they have borne much of the additional work. This is just a guess, however, since the data to confirm it is not yet available.

There were very negative consequences also for “immigrants and people working in the informal economy”, said Garnero, “for whom we’ve seen some kind of help, but it was only temporary measures and mostly limited to the spring lockdown”.

There is also another group of people to keep in mind. From an income standpoint, Bank of Italy surveys showed that families with self-employed people suffered a high toll, especially in the earlier phase of the epidemic. Only a small part of them declared they didn’t lose any income. And even considering the whole 2020 the situation got a little better, but still over a half of those families became poorer.

Households with retired people, on the other hand, only rarely reported losses in income. At the same time we know that in Italy the elderly were the least exposed to poverty, as opposed to young workers that have to face low incomes, unstable jobs, high rents and huge hurdles in creating a family.

The idea that a pandemic hits everybody in the same way is largely a myth. For a virus a body is just a body, but centuries of epidemics and especially the Black Death lesson taught some people that it was necessary to do something to protect their interests. As historians Guido Alfani and Alessia Melegari highlighted in their book Pandemie d’Italia, “its impact was huge because [the Black Death] caught by surprise the unprepared Europe”. Already in the 15th century, however, “the disease gained a pretty specific social trait, becoming a pestilence of the poor and centering on the humblest and least qualified”.

From an economic point of view, the two scholars showed that a mortality so high and unforeseen blew up the hereditary system in place, allowing a few people to acquire huge wealth in the form of real estate. In this confusion, many inherited fragmented and unprofitable properties from dead family members and chose to sell them. The result was higher wealth concentration, and therefore an increase in its inequality. There was also another important consequence. Since the 15th century, when things have become more stable, the largest Italian families started using a number of social and legal instruments to safeguard their assets, should a new pestilence come.

Centuries later, their echo reverberates weakly in distant relatives. Even today those deep economic and social processes make illness and poverty more frequent in the weak, the poor, those that were in a difficult position to begin with. To shake them off a little, it looks like what’s needed is the closest thing to an apocalypse humanity has ever seen.

Chapter 4. Chains

We don’t need to be seduced by the power of metaphors. A wave is a wave, an epidemic is an epidemic. One fundamental difference lies in how people behave, which is irrelevant for the former and essential for the latter. In a way a tsunami is just like an asteroid or an earthquake, and when it comes there isn’t really something we can do to make it less destructive. In this sense an epidemic like COVID-19 is the exact opposite. At the beginning there are two large hurdles the virus has to overcome: being able to jump species, and then being capable of infecting humans from other humans.

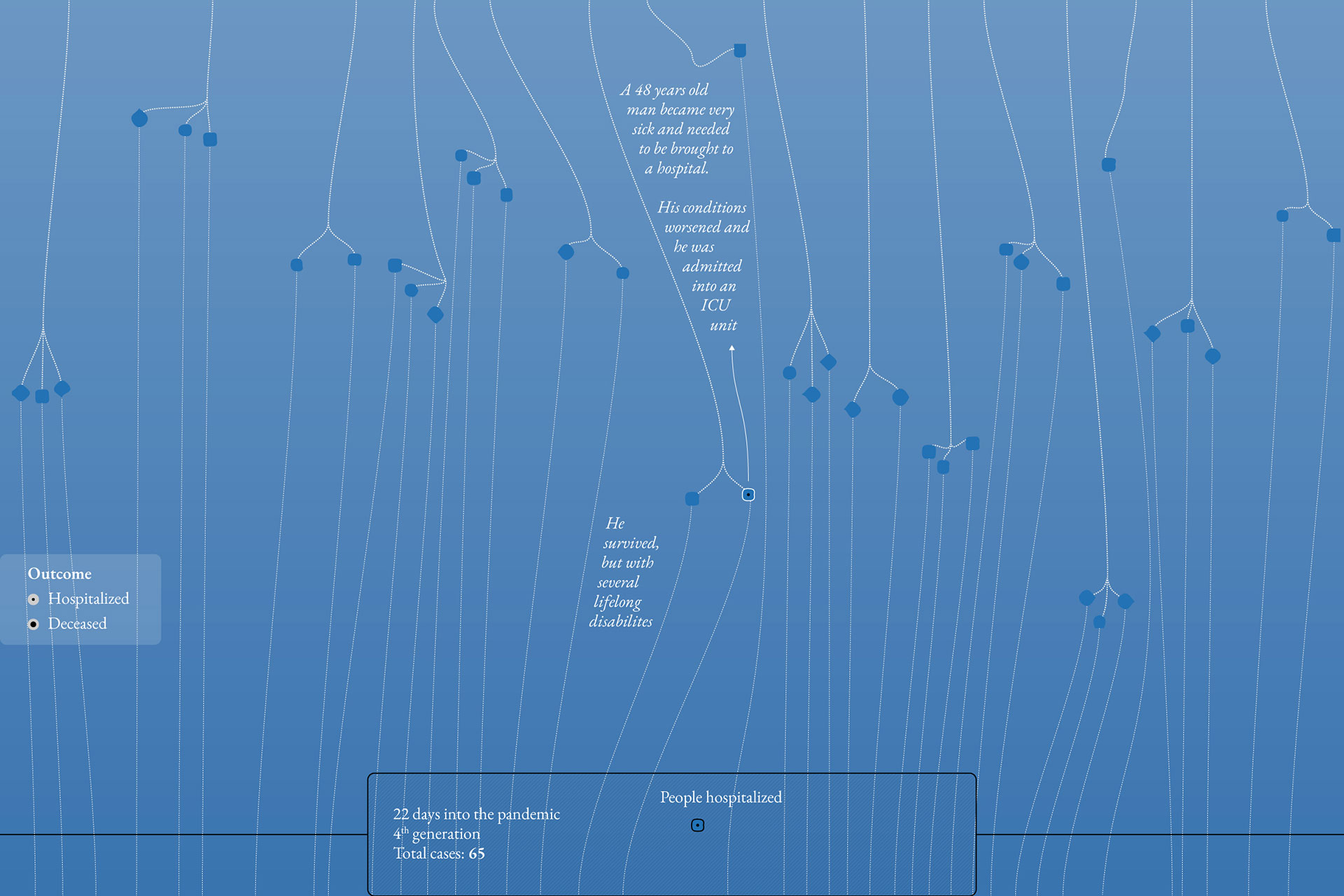

Past this, the epidemic becomes literally something depending on how people react, both in their bodies and in a more general sense in society. That’s a mechanism where the feedback is so important it becomes the system itself. Biological aspects are given in the short term, because we can’t control how our body reacts to the threat. We could try new drugs that we expect will work, based on our previous experience, but to see if they really do we need studies, scientists, patients, time.

Time itself might be the scarcest resource. If at some point we get the perfect drug that’s great for the future, but what if in the meanwhile almost everybody has been infected already? As the experience in Bergamo has showed, it took less than three months to go from patient zero to mass infection with devastating results. Technology isn’t fast enough to keep up with an exponential growth like that.

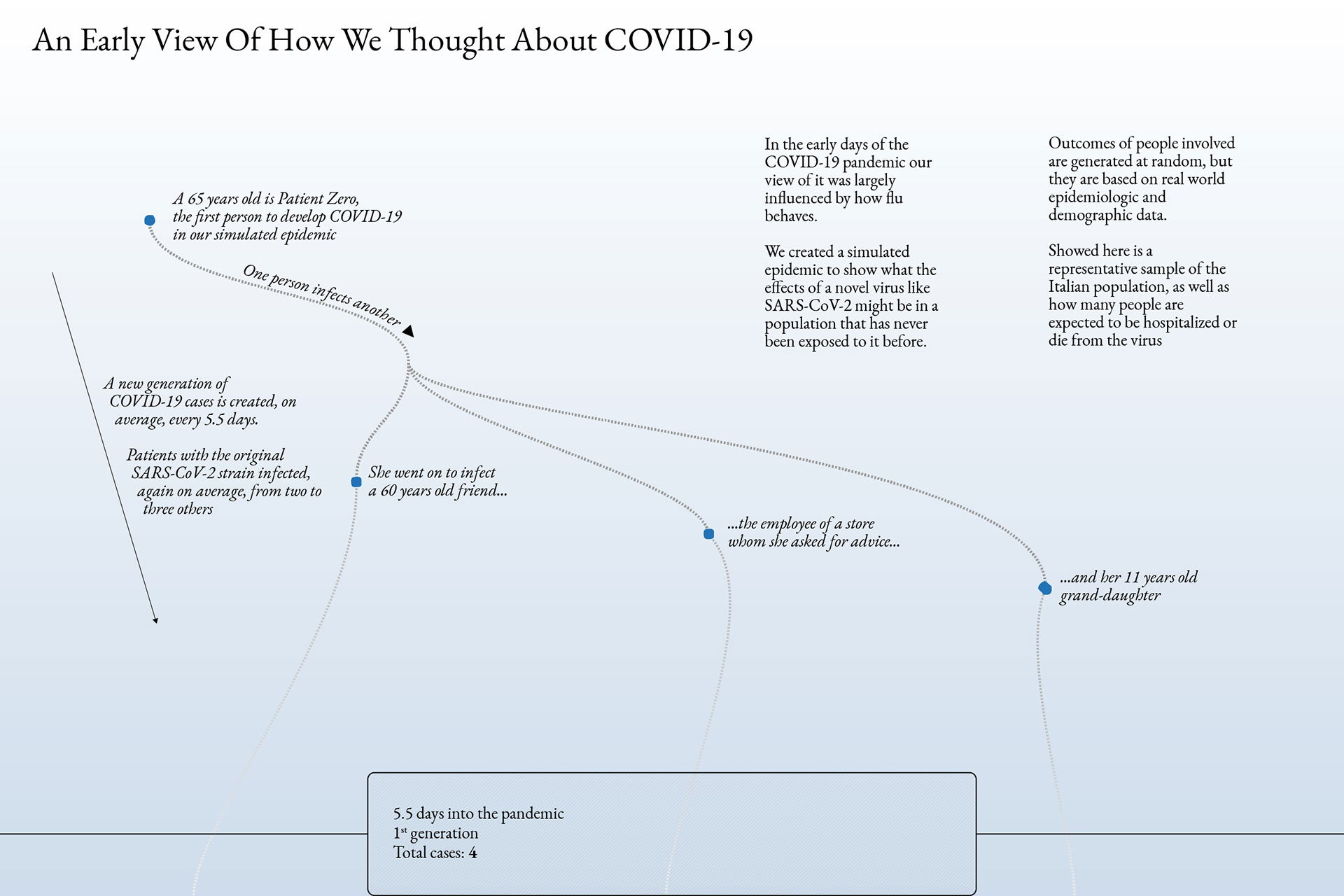

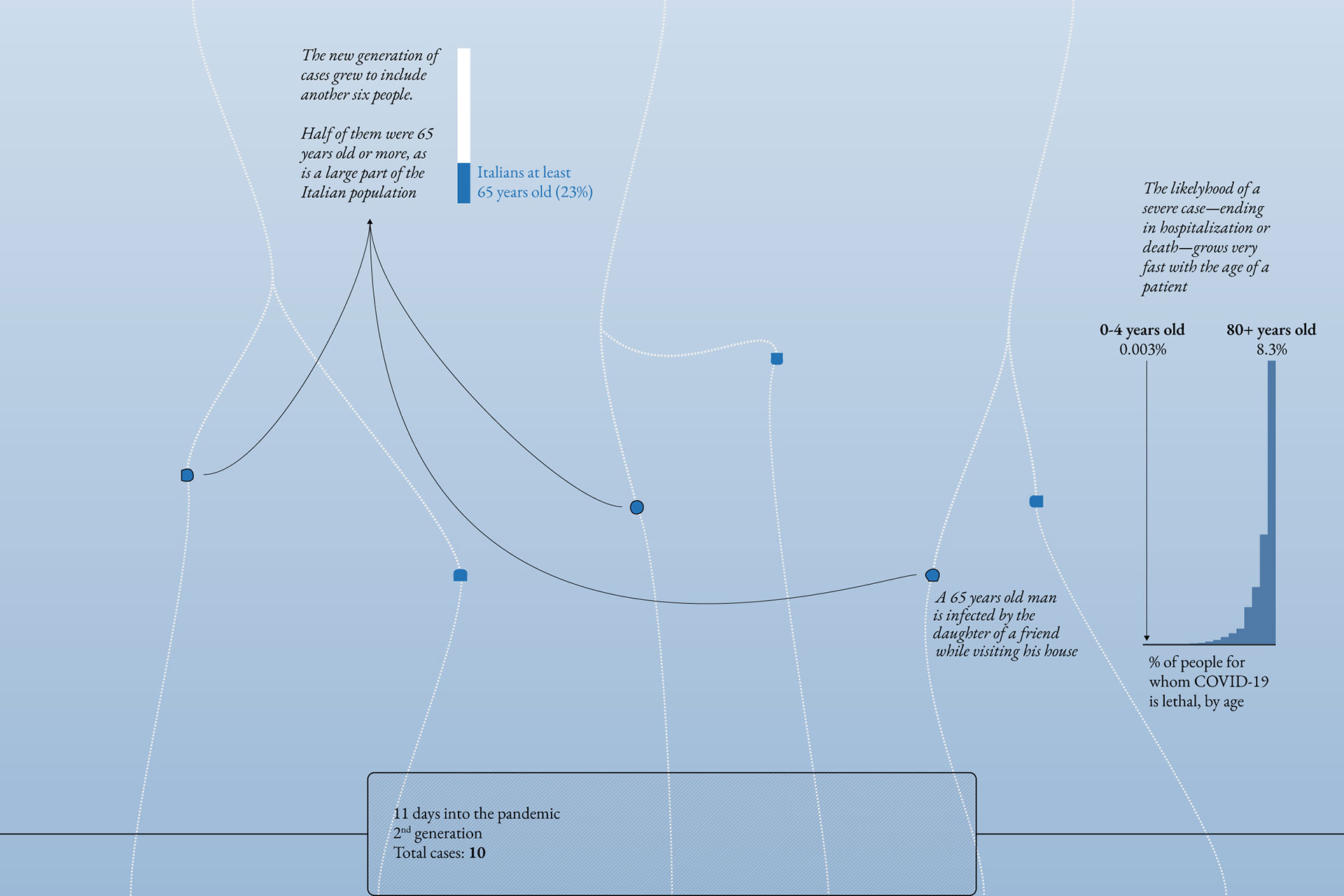

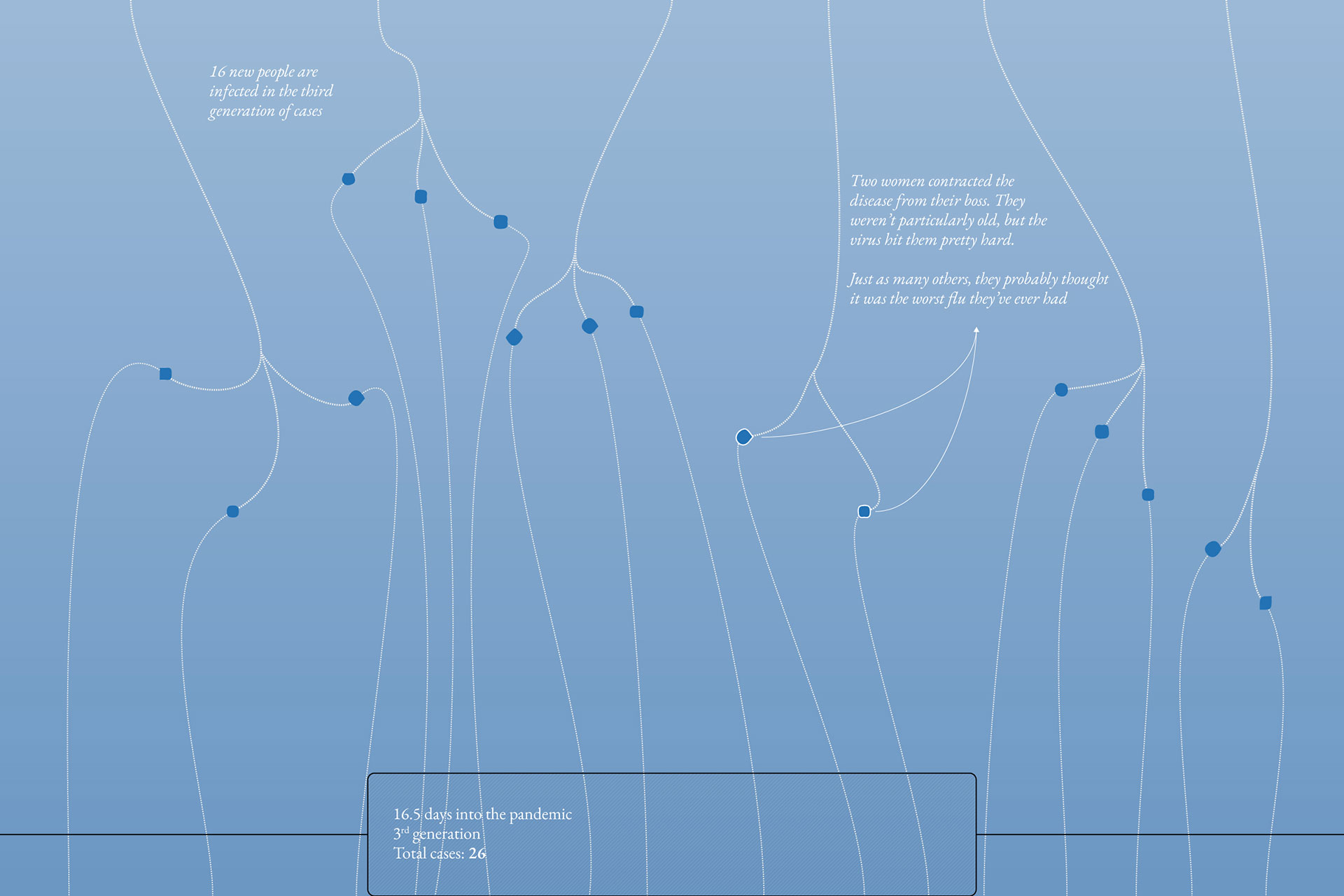

If an initial response has to exist, it has to be non-pharmaceutical. This makes of the utmost importance to understand how we thought the virus worked, how we fought it, and how our mental model adapted to new evidence. There’s an old saying according to which “generals always fight the last war”. A good chunk of this pandemic was fought against the last virus. We were the French holed up behind the Maginot Line while the Nazis were creeping up undisturbed in the Low Countries.

In the West several pandemic plans were modeled on the flu, anticipating that the next big epidemic would come from one of those viral strains. Several public health recommendations were based on this assumption, and after COVID-19 they were used and repeated to the public almost automatically.

Certainly this is a pretty normal process. When lacking information about a new phenomenon we stand on what we know already, with the idea to update our mental model as soon as new studies come. Yet the second and fundamental part of this approach was often very slow, and sometimes disregarded at all even when evidence was clearly pointing elsewhere. The problem was that flu and SARS-CoV-2 could hardly be more different.

The way we thought about the new virus was something that, like the flu, was transmitted at a pretty regular rate through direct and close contact among people or by touching a contaminated object. Each carrier would infect two to three other people, and so on. A hospital I visited recently still had one of those early public health fliers. “Remember to clean surfaces”, they suggested, “use a mask only if you suspect being sick”. These were policies that later studies found irrelevant when not flat out wrong, and that still circulated for months.

Of course this is the way science works, by baby steps and little improvements. And surely public health agencies were in a very difficult position, because they had to translate poorly understood risks into real life advice, always on the line between too much or too little. But of what use are new studies if changing our mind is so difficult? What should we make of advice that comes only after much of the damage has been done already?

There was evidence that SARS-CoV-2 was very different from a usual flu virus, and we had it early, too. On January 26th 2020, when there were only 2,000 confirmed cases in the world, Chinese scientists announced that asymptomatic people could spread the virus. Nonetheless policies often kept insisting that only symptomatic patients should get a test. On January 29th New York City Health Commissioner Oxiris Barbot told people not to listen to social media disinformation, like the idea that you could get the virus from somebody without symptoms. “There is no reason to avoid subways or restaurants or to change your daily routine”, Barbot said. A little more than a month later the city became the epicenter of the epidemic in the United States, with tens of thousands of deaths.

Thanks to the work of some of the best epidemiologists in the world, even in the early stages we had great estimates of some of the most important parameters of the pathogen: its basic reproduction number—R0. Wuhan data suggested that each case on average infected two or three more people.

On average are two crucial words. When we use this statistical concept, we expect that it will give us useful information about a distribution of values. Often that’s what happens, and it is quite a useful tool. The height of people follows our intuition, for example. Many are around the average but as we move away from it we find, more and more rarely, very tall or very short individuals. On the other hand, as far as wealth is concerned this doesn’t necessarily work. If we have a party with our friends the average value of our net worth can roughly be a good number. Yet when Elon Mask crashes our party to bum a drink his billions don’t make us all millionaires.

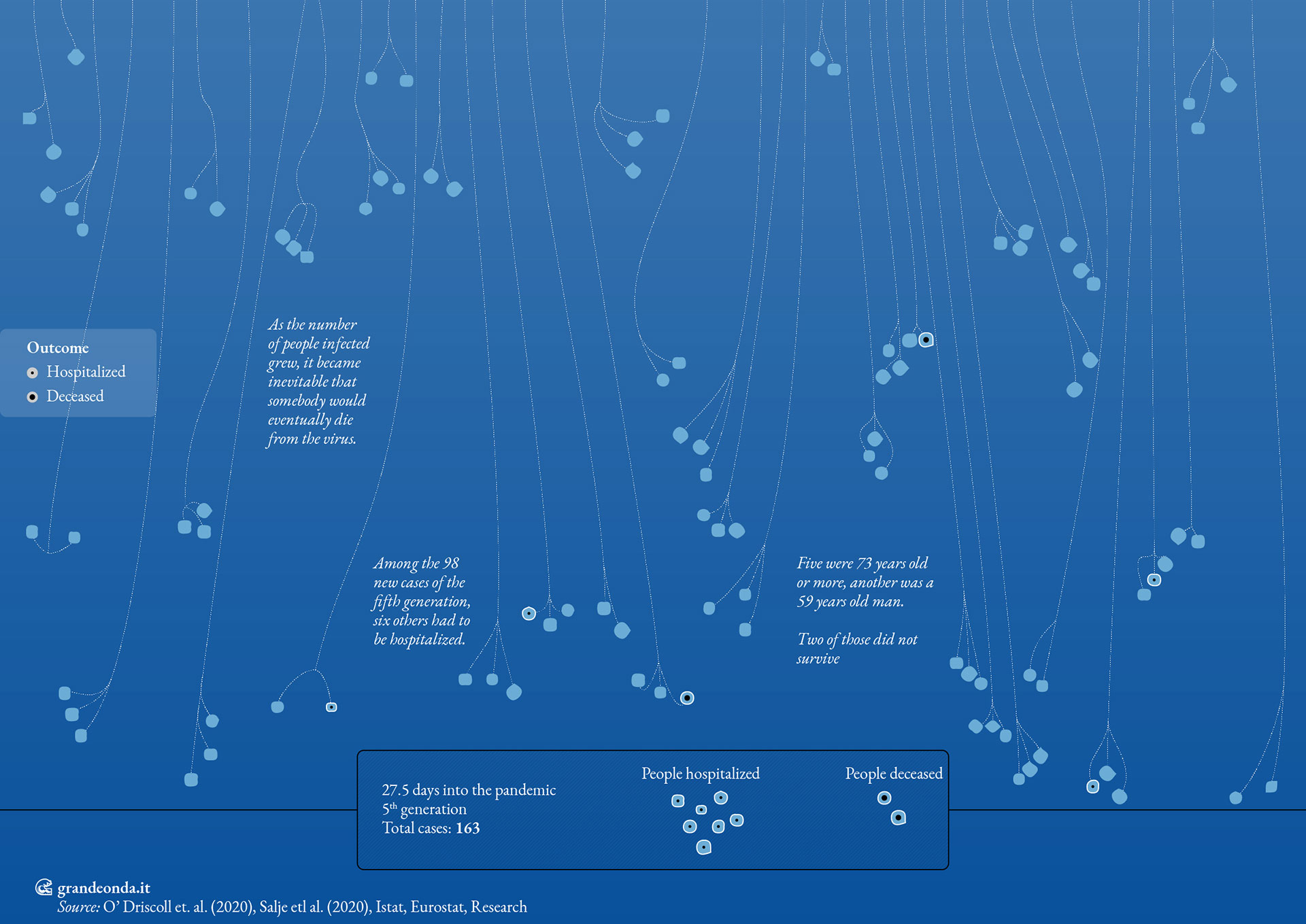

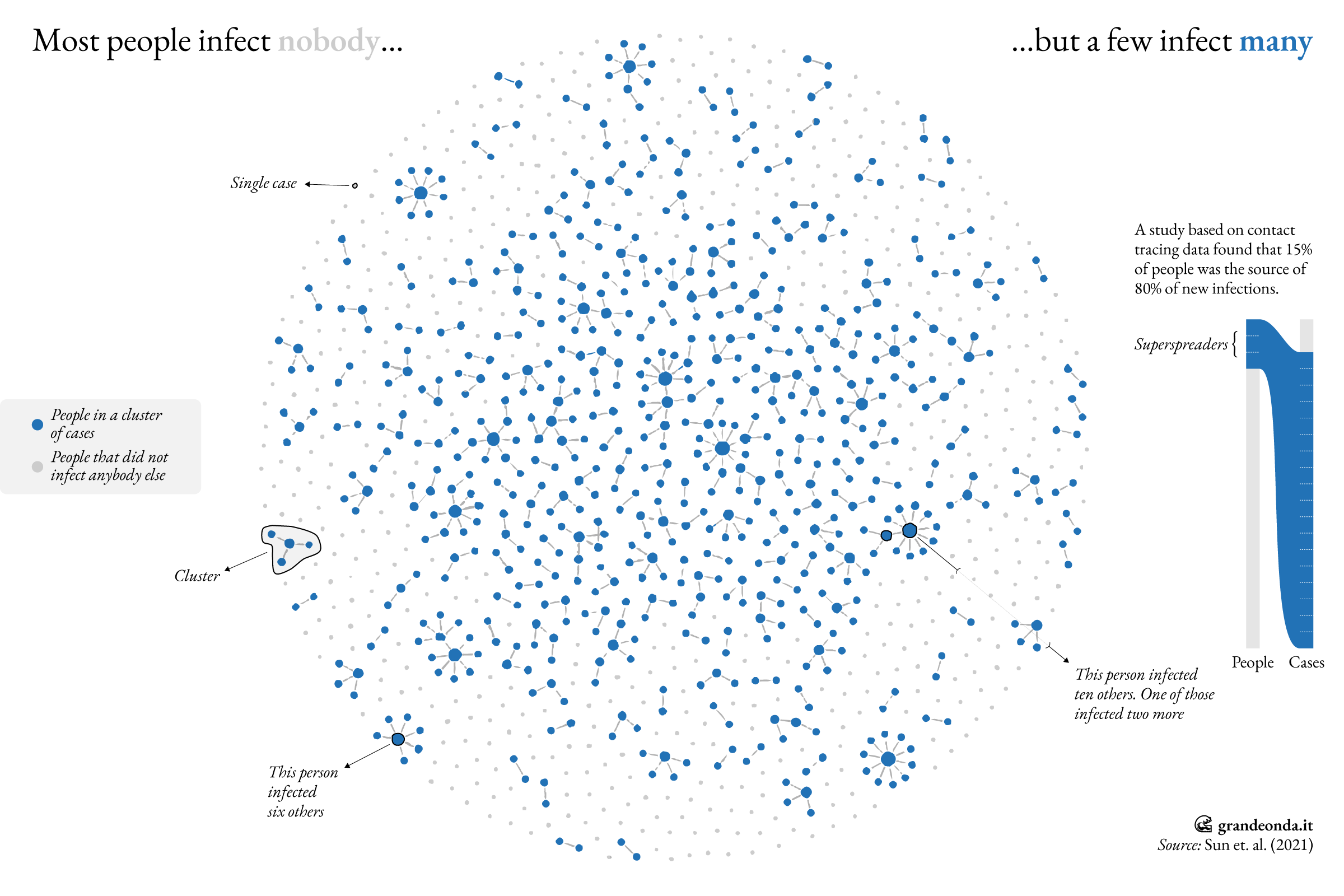

Contact tracers were looking at something very puzzling. Adding up all cases the average value of two to three new infection per case was still right, but it looked like a mix of completely different events. Most people didn’t infect anybody else, while only a minority of them was responsible for almost all infections. The virus didn’t spread gradually in small jumps like the flu, but mostly in large chunks that included many people at the same time.

Michele Tizzoni, epidemiologist at the ISI Foundation, explained that with a virus like this “the epidemic circulates with explosive superspreading events, alongside many other chains of contagion that die on their own. It means that, even if relatively rare, those events can generate many cases in few generations, thus making the spread faster in harder-to-contain localized outbreaks. When the cases go down again, it takes only a few of those events to create large outbreaks. So, generally, more virus introductions are needed to start the epidemic, but when one or two of those create a superspreading event the epidemic grows very fast and is pretty hard to stop. We had an example in Louisiana, in the United States, where according to a study just one virus introduction was responsible for all cases observed at the start of the epidemic”.

What looks like innocent assumptions can become unscientific dogmas and start a chain reaction with unforeseeable consequences. One such case was about the way the virus particles travel from one person to another. Starting from flu again, WHO and (following its lead) other national health agencies emphasized that the main route of infection was trough the so-called droplets, that is small drops that an infected person expels from their airwaves and travel directly to the mouth or nose of others. For this to work, their trajectory must make them jump directly between the two subjects, and this started a large scientific argument about “safety distance”. How many feet would that be, exactly?

A group of scientists suggested another way of transmission, that is by aerosol. Other than in droplets that move and behave like small bullets, the virus may be present in smaller particles, light enough to be suspended in the air and circulate around, pushed by currents, like a small fog. Some of them have been trying to persuade WHO to consider this possibility since March 2020, but unsuccessfully. Many grew frustrated to the point that on July 2020 they wrote an open letter in favor of this hypothesis.

Field work made by contact tracers made preconceptions obsolete again. Studies on contagion settings showed that infections only rarely happened outside, as it was to be expected if aerosols were dispersed in ventilated places. On the contrary, a number of cases popped up in which there was no direct and close contact among the people involved, not even through contaminated objects. The only thing they shared was the air they breathed.

We will have to wait until April 30th 2021 for the WHO to explicitly recognize the role of aerosols in infections.

In each of those cases the virus behaved differently from what we imagined, and the way of dealing with it should have changed, too. Often it didn’t.

As sociologist Zeynep Tufekci noted, “if the importance of aerosol transmission had been accepted early, we would have been told from the beginning that it was much safer outdoors, where these small particles disperse more easily, as long as you avoid close, prolonged contact with others. We would have tried to make sure indoor spaces were well ventilated, with air filtered as necessary. Instead of blanket rules on gatherings, we would have targeted conditions that can produce superspreading events […]. We would have started using masks more quickly, and we would have paid more attention to their fit, too. And we would have been less obsessed with cleaning surfaces.

Our mitigations would have been much more effective, sparing us a great deal of suffering and anxiety”.

Chapter 5. The Others

Most of the stories I’ve told so far are about the West. If we really have to generalize, I don’t think it’s too far from the truth to say that in this part of the planet the immediate response to the virus was largely a failure. I’m thinking about the largest European countries, but also about the United States.

At the same time, there are many lessons hidden in the huge complexity of what happened. Scattered around the world we can find good practices, big and small things that we can do starting from the—I believe reasonable—assumption that against an epidemic like this there isn’t a big idea that can single-highhandedly solve everything, but rather many smaller ones that combined together can at least help minimize the damage.

A corollary of this concept is another thing that the epidemic taught us, that is, it doesn’t make sense to think about problems and solutions in absolute terms. There are behaviors and situations that might increase certain risks to our lives as well as to other people’s, and others that to an extent might mitigate those risks.

The most obvious example is probably the school. We are well aware that children can get infected and infect others, just as we know very well that closing schools will be hugely damaging for them in future, and more so for kids that come from disadvantaged backgrounds. That’s why maybe it is less helpful to think in absolutes than look for ways—if they exist—to lower that risk.

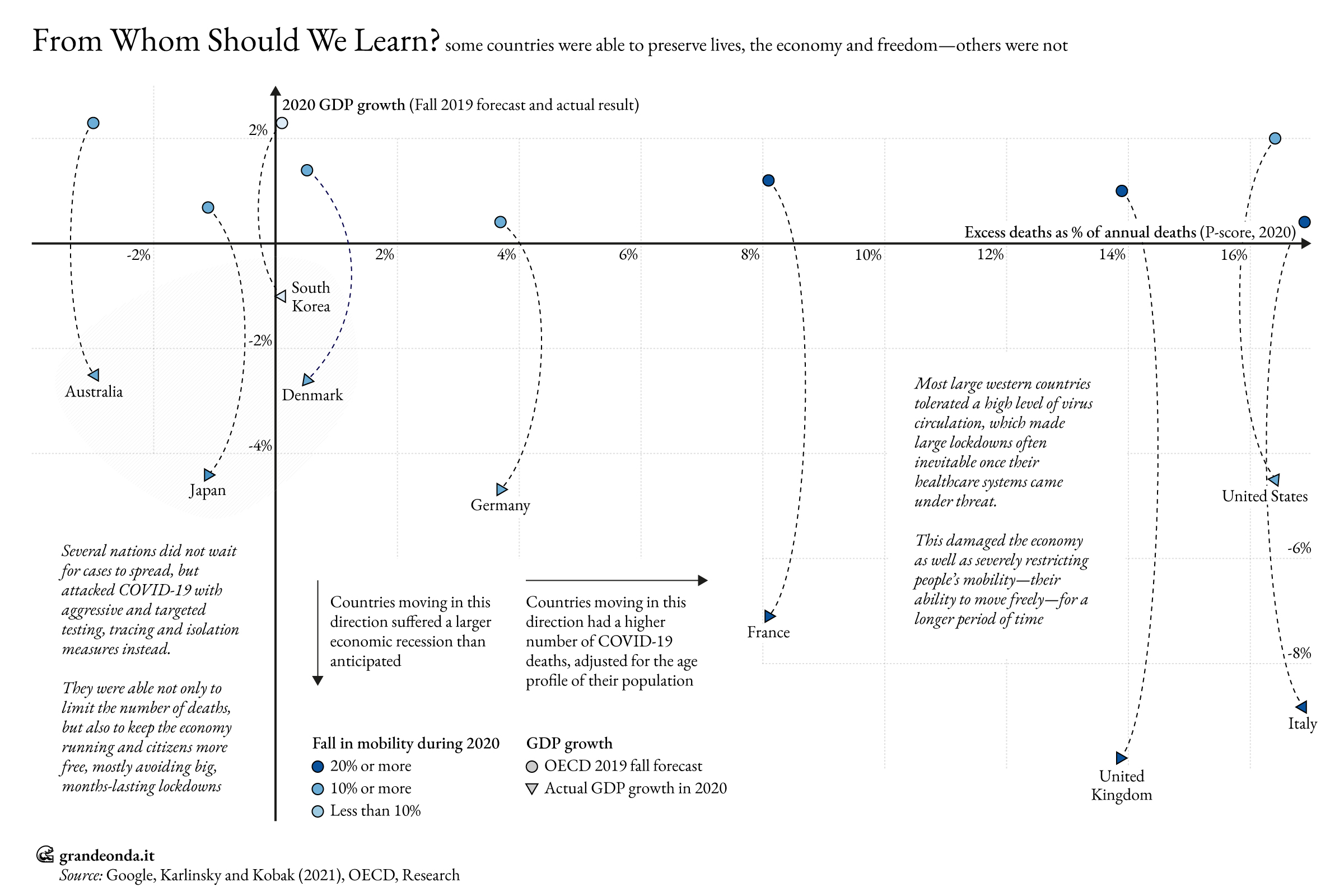

The reason why it looks pretty clear to me that the West has failed is that there in 2020 the epidemic brought the worst of the three worlds. From a health standpoint the number of deaths was huge. That made big lockdowns inevitable, which in turn damaged the economy and greatly restricted individual freedoms.

Some, even in Lombardy, suggested a trade-off between health and the economy. “Milan doesn’t close”, we heard them say. We need to keep open, because otherwise how will families and companies survive? Yet studies showed that this was not true. Countries that were able to keep virus circulation at a minimum weren’t forced to adopt hard and month-long lockdowns like others, and preserved lives, economy and freedom at the same time.

What changed was the tolerance against the pathogen. In the West the prevailing approach was not to close anything until it could not be avoided anymore, thus accepting a much higher level of virus circulation. Elsewhere, mainly in Asia but not only there, even just one untraced case spelled danger because they couldn’t know where it came from and how to navigate its chain of transmission.

We grasp the difference in approaches if we think of the case curve like a plant that spawns poisonous fruits at an increasing pace. In one strategy we cut off as many bad branches as possible, stopping the expansion in its tracks. Indeed, some will escape because human error is always possible, but a few only cause little damage. In the other strategy we wait and wait until the bad branches break into our windows, but at that point there are too many and all possible gardeners wouldn’t be enough. We just have to weed everything out.

Those who thought to scrape along by doing nothing found themselves under a huge pressure in a very short time, and that forced them to close way more than what they would have to otherwise. This is why where there was little virus circulation lockdowns tended to be intense but limited in time, and people were often more free. Reaction against prevention.

A big national lockdown is an amputation after all, the second worst decision besides doing nothing. It’s a desperate acknowledgment of failure, when you couldn’t, didn’t want or weren’t able to do better, and now you only have one alternative—sacrifice a hand for an arm, a foot for a leg.

Difference is, this time whole nations became gangrenous, one chunk at the time.

Couldn’t, didn’t want to and weren’t able to are the three key concepts in trying to weigh how countries responded to the virus. Now don’t get me wrong, the story of the plant and its branches is very cute, but let’s not kid ourselves. Comparisons are very hard, and the conversation about what was the right response will keep the next generations busy for decades. There are no obvious solutions. Each of those measures is complicated, without precedents in generations, hideous in principle because its purpose is making us less free. It’s not about cheering for one or another, because truth be told they all are horrible, but only about trying to understand which one hurts less.

Paraphrasing the famous saying, epidemiologists love to joke that “if you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen… one pandemic”. Inside them someway there is the whole human society with all its immeasurable complexity, and so we just can’t copy paste strategies from countries too different as for geography, culture, and so on. It’s not obvious at all that something that worked in one place will work elsewhere. For each approach there must be the right circumstances, like contact tracing that is feasible only if the number of cases is very low.

This is a good argument, but if taken too far it might lead us to fatalism. If every useful thing is unrepeatable and works just once in its context, then there is never a lesson to learn. Why would we even study pandemics? On the contrary if we look for good examples we can find many, and to think otherwise we risk the sin of arrogance in justifying our mistakes because there really wasn’t anything we could have done.

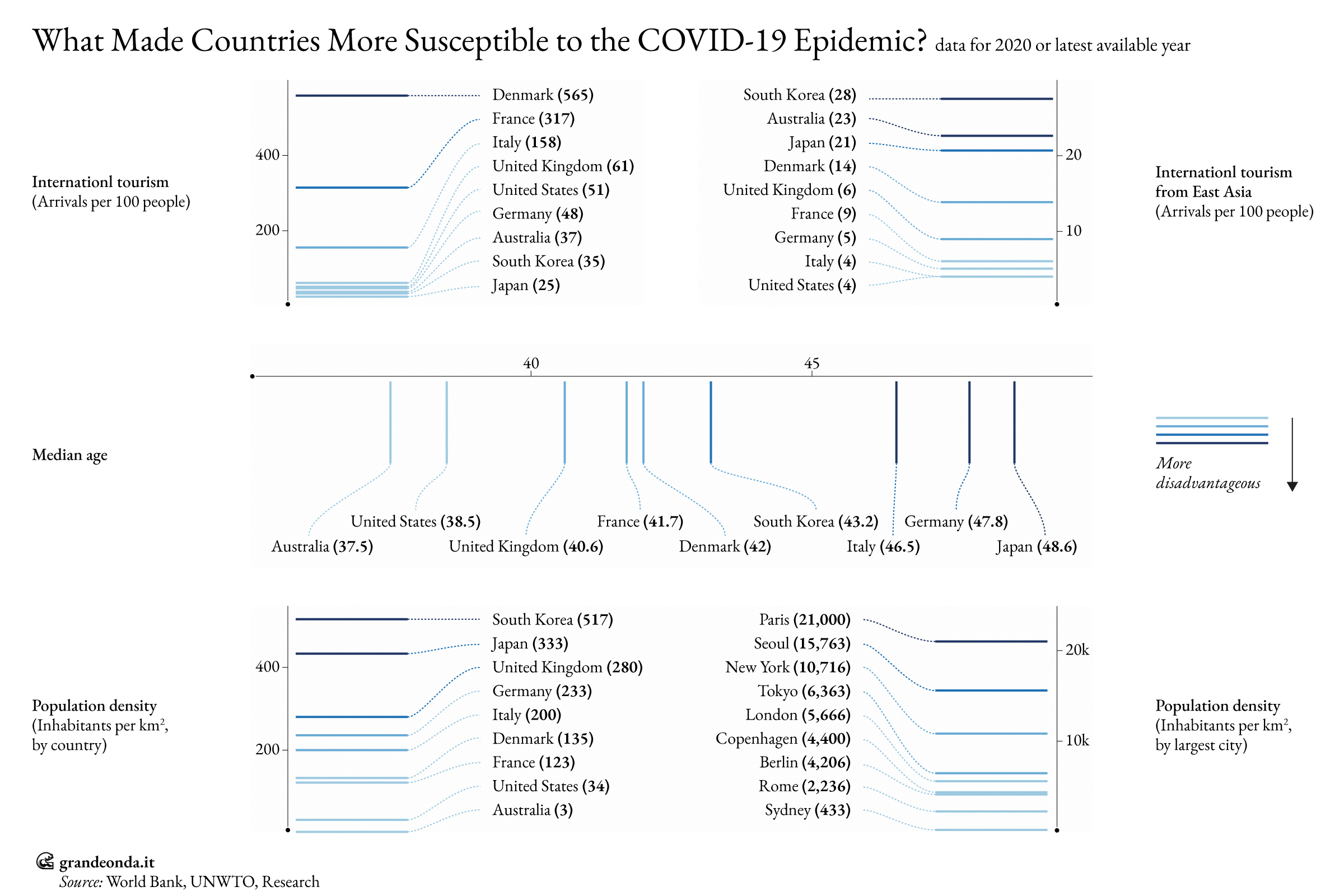

The conversation about the couldn’t must note that the initial conditions were very different. There were countries in which social contacts were very frequent and diversified, and others where the opposite was true. Places where the young and the elderly often met, and others where that rarely happened, with all the obvious consequences when it came to infections. France—and to a lesser extent Italy—had a lot of tourists, which made it more likely to have an introduction of the virus from abroad. On the other hand, people living where the pandemic started tended to visit other parts of Asia and Oceania more often, and indeed those areas had the first documented cases outside China.

Italy had a pretty old population, which increased the risk of a virus so dangerous for this age group. Surely if we get to this point it also means that the infection has spread and the testing and tracing system has failed already. “Older countries were hit harder because of the age gradient in the death risk of the virus”, said Ilaria Dorigatti, epidemiologist at the Imperial College London.

In theory even population density could matter, with some countries that have people living way close to each other and nations where the population is more dispersed. It is interesting to note, though, that among the firsts there are South Korea and Japan that had a very low number of cases. Japan is an island, which is an advantage, but then what about the United Kingdom?

“As a general rule”, explained Francesco Di Lauro, epidemiologist at Oxford, “observations about population density and the spread of a pathogen are difficult because density can be very heterogeneous. Yet, if we look at a smaller scale (metropolis, large cities, perhaps even regions), the distribution of the number of inhabitants gets closer to average and it starts to make more sense. In that case we can easily correlate population density to the spread of a pathogen. It’s no coincidence that superspreading events rarely happen when there are few people around after all”.

“SARS-CoV-2 is a virus especially transmitted in enclosed and poorly ventilated spaces”, added Dorigatti, “so it’s not surprising that population density is an approximation of the number of contacts. Countries with higher density had epidemics with a larger basic reproduction number”. Yet, she said, it’s clear that choices, policies and a quick and timely reaction are key in controlling a new virus, and not only at the beginning but also in all stages of the epidemic.

Those differences among countries do not necessarily mean destiny. There’s little doubt that without their solid testing and tracing system, all else made equal, the situation in some countries would have been way worse. Several nations are denser than Italy, and many cities in the world are denser than its towns. Germany and Japan are older, but they did better. And as much as we’d love to, it’s not like we can make Italians younger. There is no alternative but to work with what you’ve got.

“I don’t think Australia had all the advantages we might believe”, Di Lauro considered. “Of course, you can reach it only by plane or boat, while you can go to Italy by car, too. But I don’t believe that Sydney, Brisbane or Melbourne are little frequented places. Furthermore, Australia has 25 million inhabitants, but a fifth lives in Sydney and another fifth in Melbourne. They are big cities, more than the metropolitan area of Rome. One advantage is that their cities are quite apart from each other, and this makes it easier to implement local controls. In Italy everything is more fluid, as between Rome and Milan there are infinite medium sized cities and therefore more travels and connections. This has to do with the efficacy of the pandemic response, because clearly it is easier to control isolated hubs than to check city by city.

That said, I believe that without its strategy Australia would have had the same fate as Italy. At least that’s what it looked like before they went into lockdown in 2020”.

If we take a look at the didn’t want to, the will to actively respond to the pandemic, we find very little. This means that basically every measure that required a modicum of re-organization or change in the public sector was carried forward reluctantly, if at all.

Let’s think about contact tracing, pivotal to breaking new chains of transmission. Once big lockdowns were over, during summer 2020, cases were back to a pretty low level in Europe. That might have been the time to strengthen contact tracing, but on the contrary it was snubbed and at times even cut off. Digital tracing apps were found as another potential useful tool in avoiding cases, but only few countries developed, promoted and used them. In Italy and elsewhere they were a failure. Schools were more the target of political controversy than anything else, and there were very few actual projects to secure them. The list goes on. In short, Western countries often dumped the whole burden of the epidemic on citizens and healthcare systems—at most just reacting, or closing up stuff and passively waiting for the storm to pass.

This is not the place for a long and complicated discussion about whom drives whom, that is, if politicians acted on their own, or they didn’t have popular support for more aggressive measures, which in turn made them politically unfeasible. There are sensible arguments for both sides, but it’s hard to deny that in countries like the United States the resistance to even very mild measures like using masks has deep roots.

We can only speculate about the why. Maybe it’s because the West hadn’t seen a true pandemic in a century, while other Asian countries after the SARS scare developed plans to act once it would happen again. Considering what they did, at times the comparison becomes embarrassing. In the 2011 UK pandemic plan there were phrases like: “it will not be possible to halt the spread of a new pandemic influenza virus, and it would be a waste of public health resources and capacity to attempt to do so”. Others looked like pure theoretical exercises without a single practical measure, as if they were talking about an alien invasion and not something that had happened and would have happened again. In one of the Italian documents the words “tracking” or “tracing” never appeared.

When the virus finally arrived, we actually did what the plan suggested—nothing.

Lastly there’s the problem of the we weren’t able to. There are many examples for this, and most come from the understanding of how the virus actually works, which the West stubbornly slogged to accept even after months. Elsewhere in January and February 2020 the pandemic response was already based on many of the fundamental principles: asymptomatic transmission, mask use, superspreading events, air ventilation and filtering in closed spaces, advanced contact tracing trough apps and other digital tools to piece together chains of transmission. (As always, each tool has advantages and disadvantages. The use of extensive and sometimes invasive surveillance techniques also led to some excesses, with serious concerns for the citizens’ privacy.)

In March 2020 we could read stories about how using face masks was basically a superstition, while Japanese factories started mass producing them on January 18th. The day before health authorities advised Hong Kong residents to avoid crowded places and those with poor ventilation, months before the idea of airborne transmission would be even considered in the West.

Looking at how transparent governments were with information, the difference in approach is also stark. There were countries that set up platforms driven by contact tracing data in order to look for cases in the area we live. This is to be meant literally, as if a case is discovered in the bakery near my house the map will point exactly there, so that I can contact somebody in case I’ve been there recently.

In Italy the philosophy couldn’t be more different, and besides some lucky exceptions the best possible scenario was knowing if there was a case in a whole given province. The issue here lies at the top. The most important data about infection and patients was assigned by law at the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS). The institute let out only the bare minimum of information only after huge pressure and almost never in open data.

At some point for this project I got interested in data about individual cases, because at least I wanted to try to make it available to the community of analysts and experts that made up for so much of what the government didn’t do. So, I used the Italian Freedom of Information (FOIA) law to write to the ISS and formally ask them for the individual cases dataset and others, namely the data used to determine the level of restrictions in each region. As I discovered by talking to analyst Vittorio Nicoletta, the greatest limits to personal freedom in the history of the Italian Republic were at times based on information never made public.

To give an idea, Lombardy has been in a higher tier of restriction for a week because of an error in the data. Maybe somebody on the outside could have noticed it. It’s not at all a theoretical issue, this is what transparency is about.

In theory public agencies are supposed to just give what asked. The story of how my request to the ISS went is pretty long and complicated—I was after them for months—, but I guess I can paraphrase it this way. I went grocery shopping and asked for apples, pears and bananas. I needed those exact fruits for my recipe, and I knew they had them because I checked before going. They said they didn’t sell berries, but had some watermelons. I replied they maybe they misunderstood, I asked for apples, pears and bananas. They surely had to have them because I saw a truck bringing them in. And they were just there, on the counter. I protested. The guy didn’t miss a beat and replied: “we have some great out of season peaches”. After a while I got an email from the store manager saying that my protest was rejected because I had watermelons and peaches available, just like I asked. Why was I still complaining? Curtains.

There are two possible way of translating answers like that, and perhaps it’s better to believe in bad faith. Whatever the reason, those must be excuses to not provide the data. The alternative—that the most important scientific Italian institute in fighting the pandemic can’t tell apples from watermelons—is terrifying.

As a journalist I’ve rarely seen a public administration being so opaque. Truth be told, nobody ever tried to jerk me around so openly without any shame. When I talked about this with experts I got horrified responses. According to law expert Vitalba Azzollini, who followed closely the exchange with the institute, the denial to my request was groundless. “This shows how weak the culture of transparency is, and how easy it is to deny requests with reasons that only well-funded people can challenge before a judge”, she said.

“In 2021, a Public Science era, a serious public administration can’t work like the ISS”, commented Giorgia Lodi, open data expert and technologist at the Semantic Technology Laboratory. “Those non-answers should be sued. In other circumstances, with another culture, many would have been fired at the institute, and yet there they are and everything is still very closed”. Laura Carrer, FOIA expert at Transparency International Italy, said that “the case highlights once again the inability to ensure an international recognized right, such as the one to information, to Italian citizens. Journalists and citizens can work on these issues as much as they want, but that’s still useless in front of the wall raised by some institutes. Often answers aren’t really justified and people get bounced from agency to agency, losing what should be the purpose of it all: inform citizens and give them instruments to cope with fear and powerlessness”.

The funniest thing in the end is the Italian FOIA law. It should allow us to ask for information to public agencies, but if they don’t answer or jerk you around that’s pretty much the same. You can appeal and spend a few thousand euro, of course, but even legal studies I consulted did not recommend it. Sure, I might win, they said, but nothing could stop the institute from coming up with another excuse and starting it all over again.

As it is, with or without a law if the government wants to give you information, it does. Otherwise it doesn’t. That’s a whim, the opposite of the law. Citizens, journalists, scientists, activists, nobody can really do anything about it. Thinking about it again, maybe the FOIA law is not even funny, it’s just irrelevant.

I wanted the last words of this project to be about the good ideas that worked, about the courage and strength of people on the front that saved an immeasurable number of lives. Without them my mother wouldn’t be here today. Vaccines arrived faster than any of us could have imagined, and that shows that even when things look for the worst we can always keep up hope in the best part of humanity. In ingenuity, empathy and compassion, in optimism towards the future. There’s still so much to do, but those things can make our lives better.

This epidemic was about alienation and closeness, sadness and joy, despair and hope. Everything was faster than normal, more intense. It felt like living a hundred Sisyphus lives in the space of one. I wouldn’t want to ask for all that much, and honestly, I don’t even know who I’m talking to, but right now I swear I could really use even just a minute to lay down my burden.

Words Davide Mancino

Visual Design Davide Mancino & Federica Fragapane

Thanks

The Great Wave was possible thanks to SISSA – Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (Trieste) and Paolo Giordano, that generously financed it. Without them a work like this would have been inconceivable.

This project is the result of a full-time year, talking with dozen of experts, reading hundreds of scientific papers, and honestly it doesn’t even start to scratch the surface of the events. It doesn’t want to be the last word about anything, but rather the start of a conversation about what happened and what to do when it will happen again.

Besides the interviewees, that helped me way more than it can be guessed by just reading their answers, I wish to thank Marco Albertini, Guido Alfani, Gianluca Codagnone, Giovanni Federico, Silvia Francisci, Ariel Karlinsky, the Lisi legal study, Gianluca Macchiarola, Mattia Marasti, Stefano Mazzuco, Vittorio Nicoletta, Megan O’Driscoll, Daniela Paolotti, OpenCovid-mr, Lorenzo Ruffino, Fabio Sabatini, Chiara Sabelli, Andrea Spizzichino, Aureliano Stingi. A special thanks to Beatrice Dalle Rive and Francesco Zarrelli for their time and friendship.

Video credits: Naturaleza Viva e Relaxation Windows 4K Nature. Music: Bio Unit – Ambient 1

Technical annex and sources

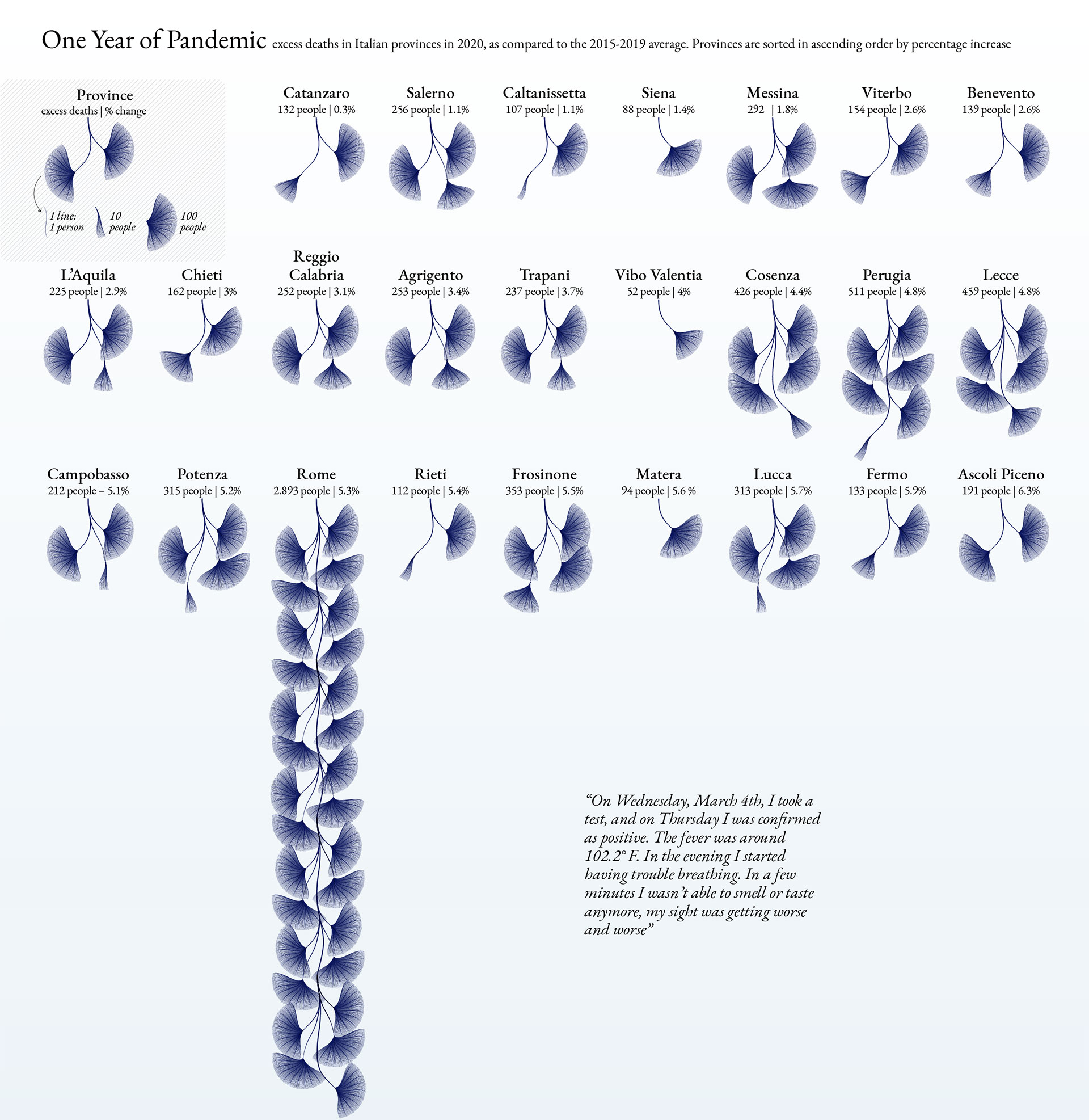

Chapter 1

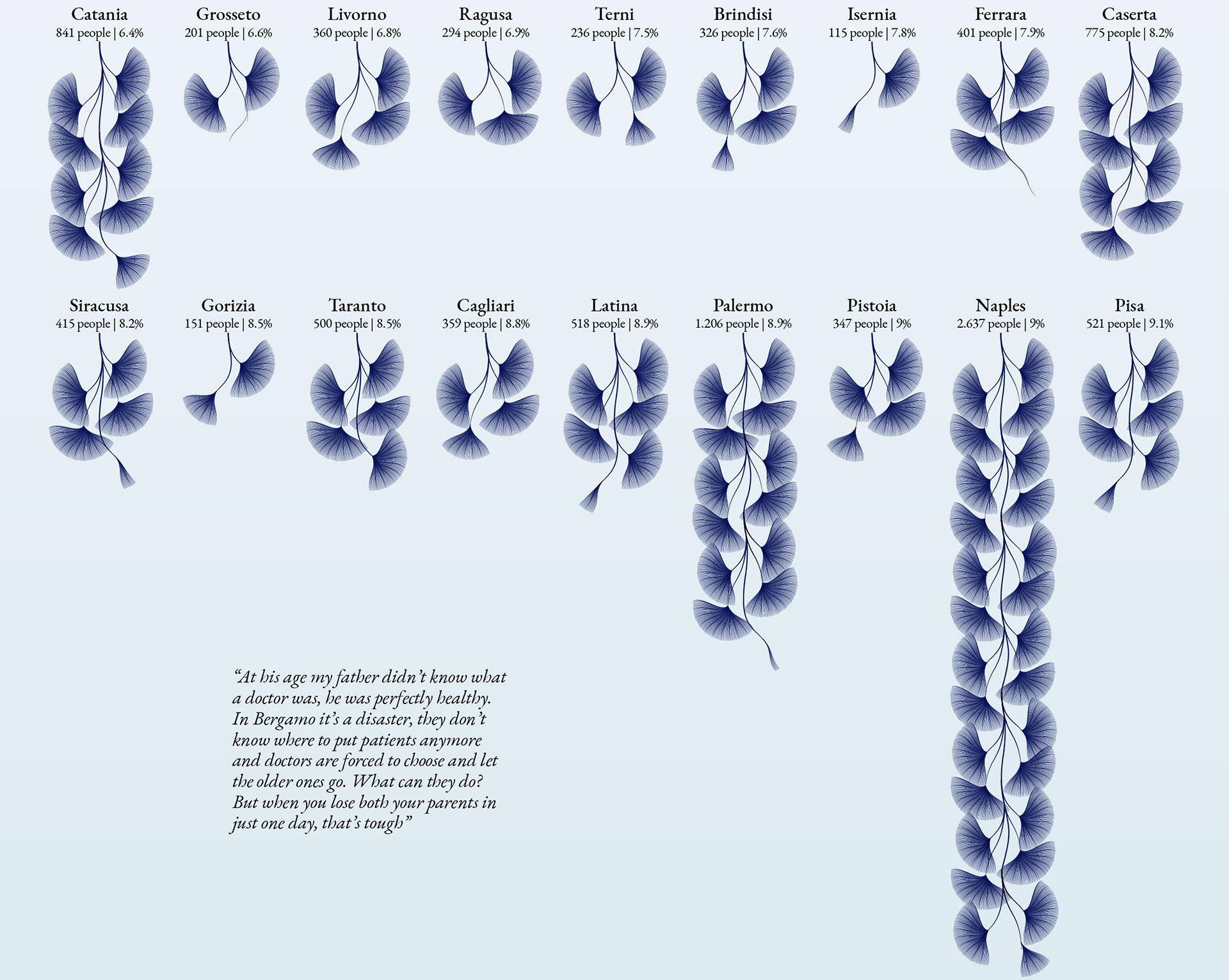

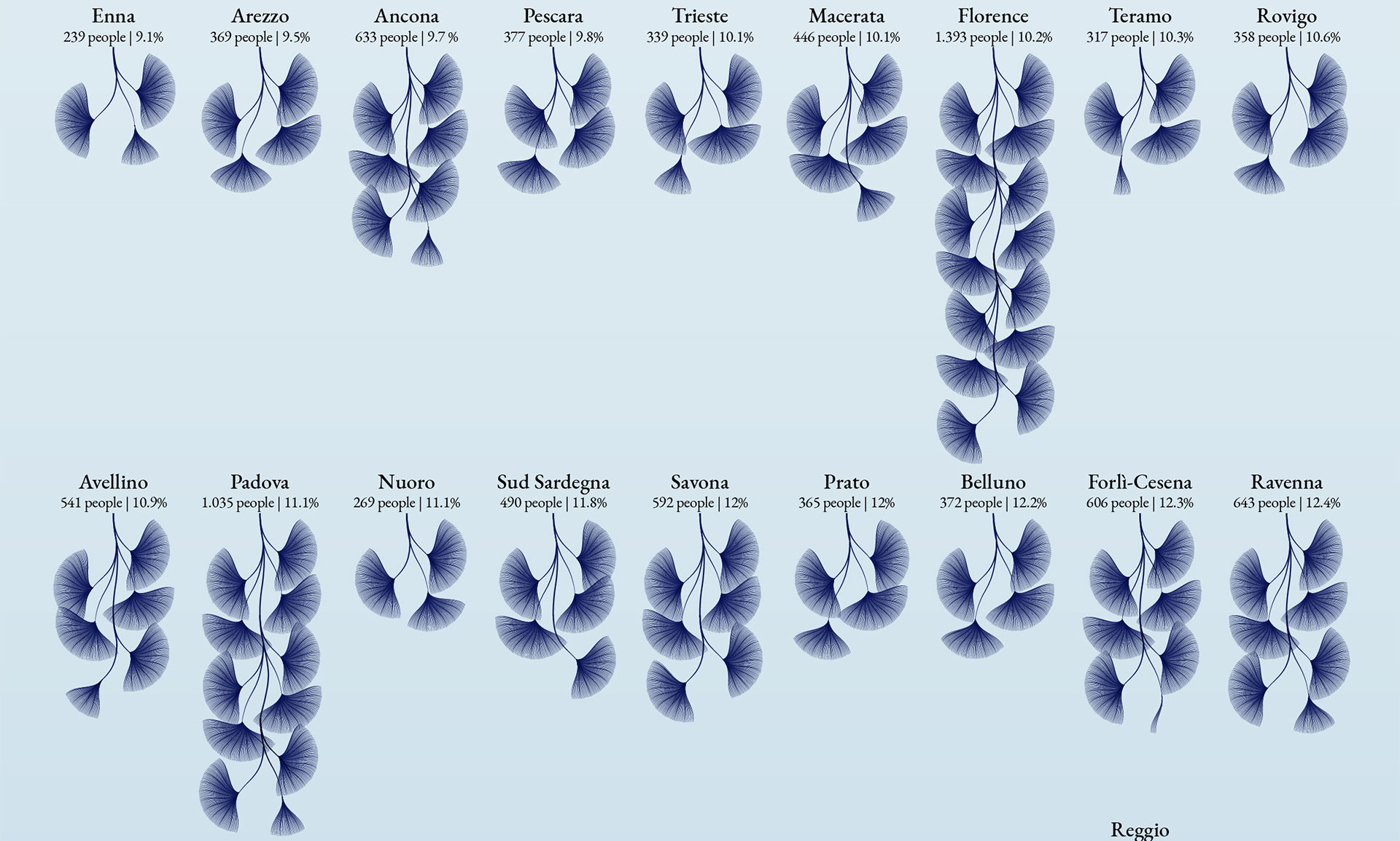

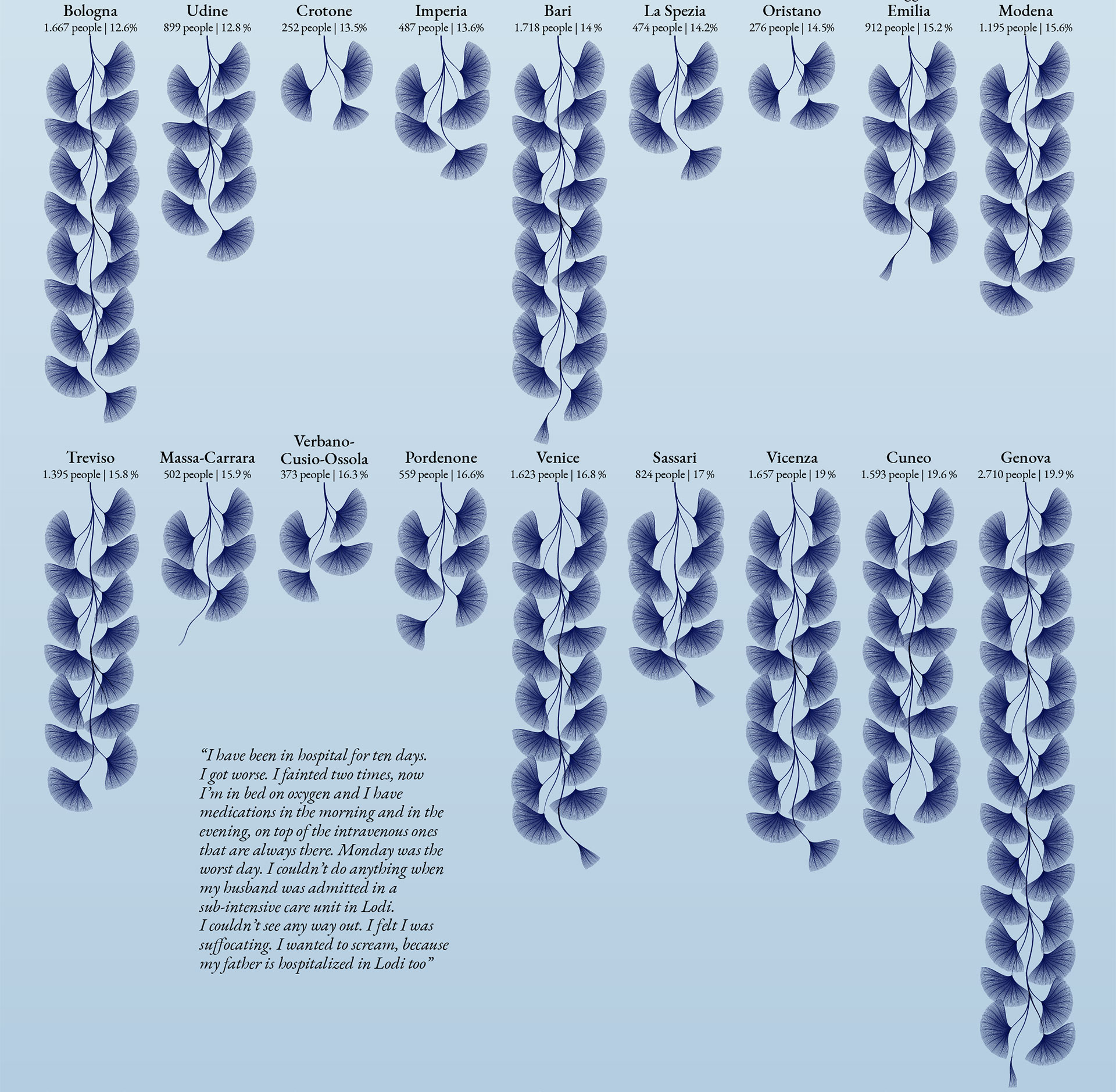

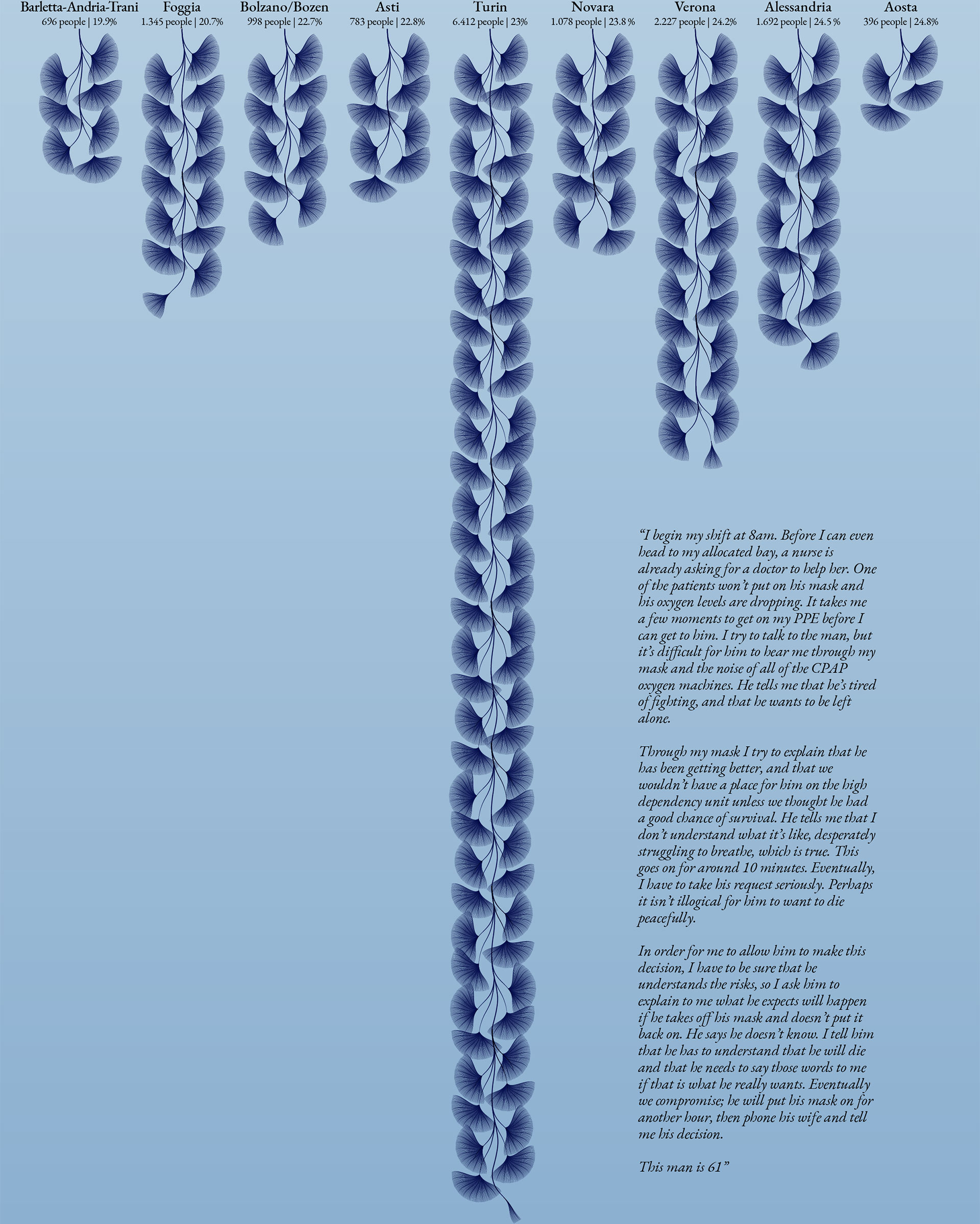

The first three visualizations of the first chapter are based on Istat data on daily mortality in Italian cities by age. Here as in the rest of the project decimal numbers were approximated to the nearest integer when they had to be visualized. Excess death is calculated as compared to the same month of years 2015-2019.

To create the final visualization of the chapter, starting from 2020 demographic data and census data, I estimated the family structure in Bergamo and, by stratifying it by age, I applied it to excess deaths in March 2020. From there, considering some epidemiological parameters of SARS-Cov-2 like its age stratified infection fatality rate, age stratified hospitalization rate and household secondary attack rate I simulated a possible distribution of the families of the dead. Families of cohabitants were created based on the Istat definition of the concept. The end result was double checked as much as possible against real stories as told by the news. For obvious privacy reasons we’ll never know exactly who those people were and whom they lost, but I felt it was my duty to at least try to paint the best picture possible.

The interviews of this chapter have appeared on Il Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica, Il Post and the BBC.

If you want read more about what happened in Bergamo during the first months of the pandemic, a great starting point is the book (in Italian) Bergamo e la marea, by Davide De Luca. The Twitter account Covid One Year Ago offers an interesting chronicle of the very first days.

Chapter 2

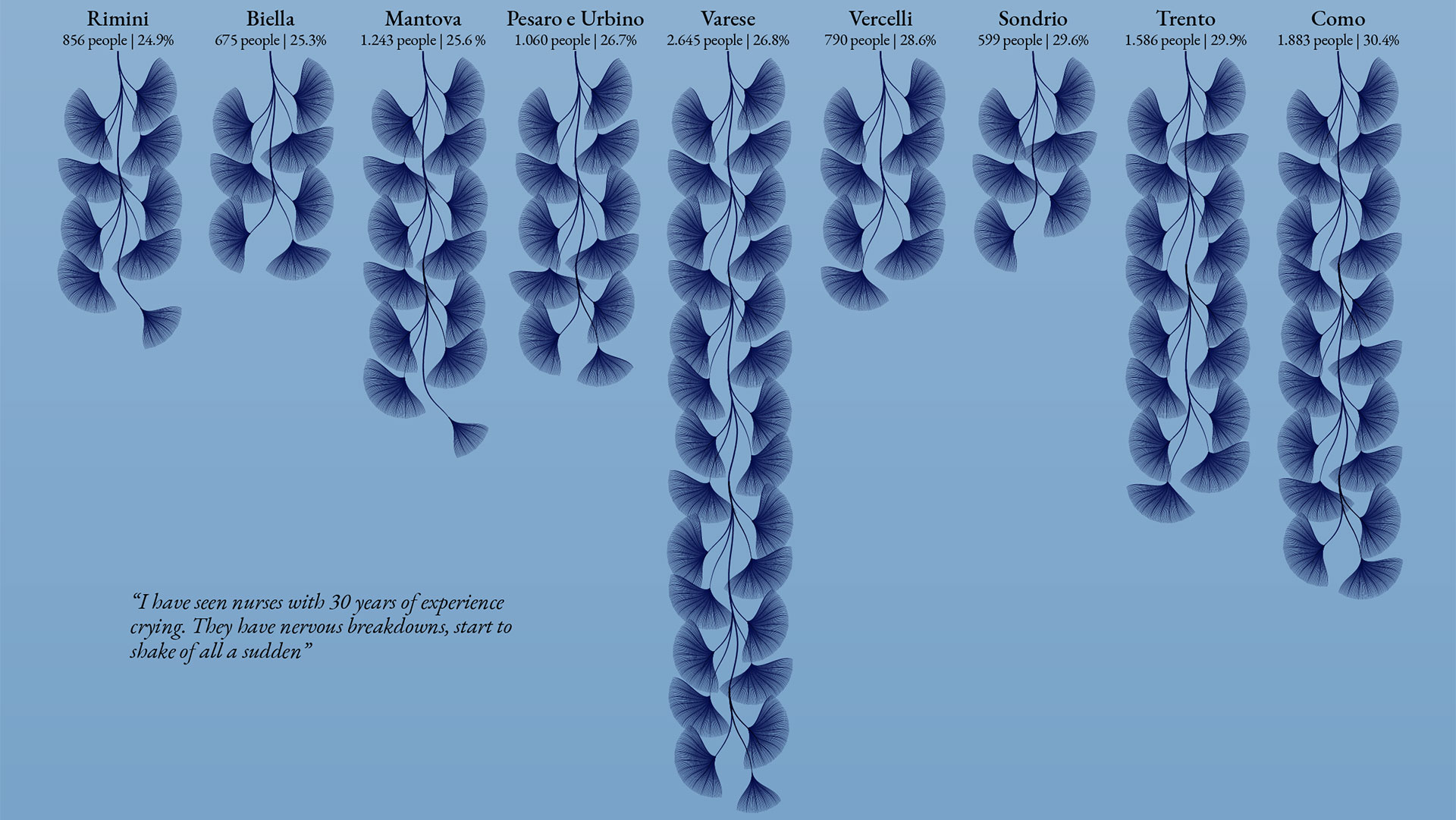

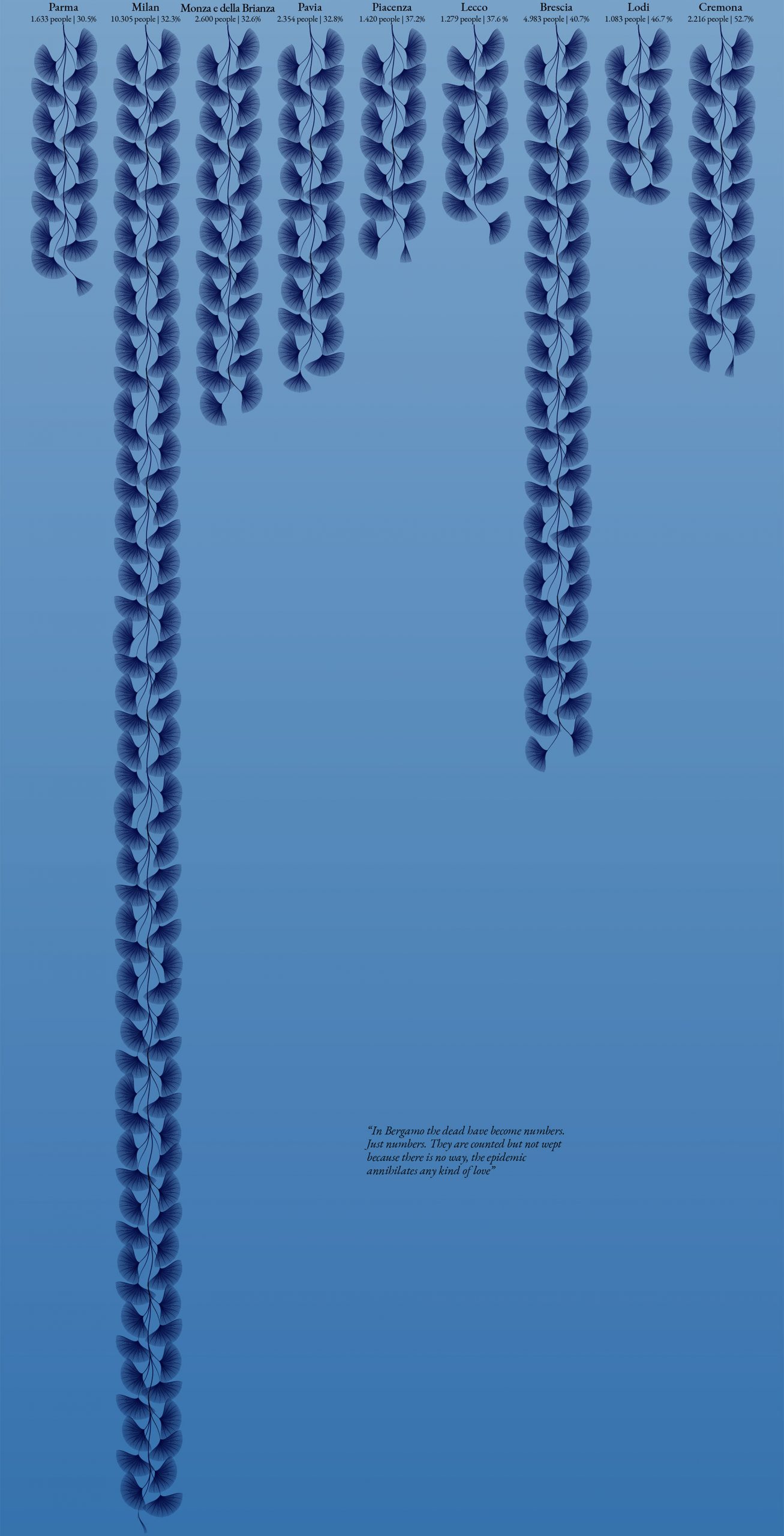

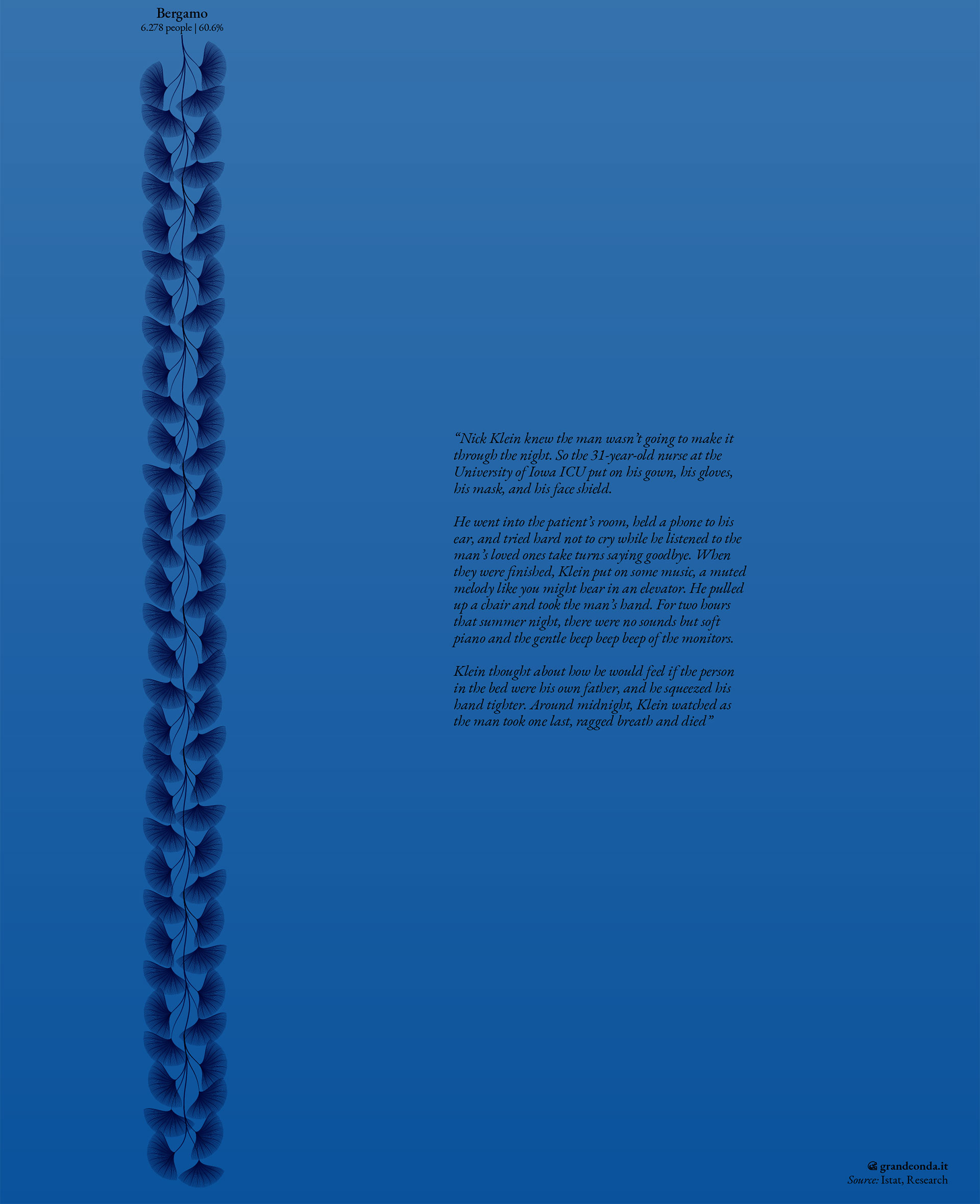

The first visualization represents excess deaths in 2020 compared to the 2015-2019 average by province taken from an Istat dataset. Excerpts are from paper stories by Il Corriere della Sera and La Repubblica, others from The Atlantic and Unherd.

Visualizations about Long COVID are based respectively on a systematic review of symptoms in mostly hospitalized patients and on data compiled by the British Office for National Statistics both for prevalence as compared to a control group and for the effects on mental health. I cannot stress enough how difficult to measure those are, especially when it comes to mental health. I spent quite a lot of time with experts trying to understand which numbers were the best available and their limits, but still the ones I reported must be considered as provisional evidence that surely will change in the future.

Chapter 3

The first visualization used data about quarterly employment rate and the total number of people employed by citizenship, gender and age class, compiled by Istat.

The second one is based on three special surveys on Italian families by the Bank of Italy.

Chapter 4

In the first visualization I simulated the first phases of an epidemic of a virus with the characteristics of SARS-CoV-2, modeled on a population with the same demographic structure as Italy. Epidemiological parameters refer to how the virus was in early 2020, that is with an R0 between 2 and 3 instead of 5-8 as studies now suggest for the Delta variant. The age stratified infection fatality rate and hospitalization rate come from the studies cited above.

The chart about the way infections are distributed is based on a study published on Science. It is not a systematic review, and it’s likely that in other papers there will be fluctuations of the k parameter (which measures the dispersion of new infections). Nonetheless it’s pretty clear that superspreading events hold a special place in understanding how this virus spreads.

One of the most glaring proof of aerosol and airborne virus transmission is this Korean CDC study, whose results I used as a base for the video in the fourth chapter. Subsequent contact tracing found similar patterns, suggesting that the role of airborne transmission was more important than we imagined.

Chapter 5

Sources for the first visualization are as follows: data for excess mortality in several countries in 2020 were sent to me by Ariel Karlinsky of the Kohelet Economic Forum (Isreal), as part of the World Mortality Dataset project. GDP growth forecast and actual GDP growth in 2020 are from OECD. The reduction of people mobility, used as a proxy of the restriction of individual freedom, was calculated from Google mobility data as an average of all available indicators except for homes and parks.

The last visualization is based on data made available by the UNWTO for international tourism, by the World Bank and my research for population density in countries and cities.

THE AUTHOR

Davide Mancino (1983) lives in Turin, Italy. He is a visual journalist, information designer and trainer. His collaborations includes news outlet in the United States like Fivethirtyeight and Quartz, others in Spain and Germany. In Italy he writes for Il Corriere della Sera and Il Sole 24 Ore. You can find him at [email protected] or on Twitter @davidemancino1.